Cambodia seems to embody all that is wrong with a developing world country. The politicians are institutionally corrupt, the gap between rich and poor is enormous, the rainforest jungle has all but disappeared, the waters have been fished out and the country is dependent on (and purposely makes itself dependent on) foreign aid. Even all the snakes have been eaten (reputedly!).

But it has two great assets that give hope for the future. The first is the people, who are incredibly welcoming, friendly and hospitable. They are deferential to authority and that makes them unwilling to vote against the current government even though they acknowledge it is thoroughly corrupt. This unwillingness stems from their Buddhist religion in which merit accumulated in previous lives goes a long way to explain a person’s social position. This also affects the way that leaders see themselves. Those in power belong in power, those at other levels of society have been born to take orders. Political affairs are seen not as the people’s business but business that occupies the time of those in charge. The people resent exploitation but hope for the best (crumbs, what other country might this describe?).

But it has two great assets that give hope for the future. The first is the people, who are incredibly welcoming, friendly and hospitable. They are deferential to authority and that makes them unwilling to vote against the current government even though they acknowledge it is thoroughly corrupt. This unwillingness stems from their Buddhist religion in which merit accumulated in previous lives goes a long way to explain a person’s social position. This also affects the way that leaders see themselves. Those in power belong in power, those at other levels of society have been born to take orders. Political affairs are seen not as the people’s business but business that occupies the time of those in charge. The people resent exploitation but hope for the best (crumbs, what other country might this describe?).

The other great asset is the ancient monuments of Angkor that bring around two million visitors per annum into the country. These monuments represent the golden age of Cambodia when the Khmer Empire was the most powerful in Southeast Asia. But these monuments have been allowed to fall into ruin and disrepair. Most recently they have been the target of destruction by the Khmer Rouge of Pol Pot despite Brother Number One using them as the reason to look upon the future with optimism, declaring, ‘If we can build Angkor, we can do anything’. Interestingly, a corollary of the idea of Angkor is that anything that goes wrong can be blamed on foreigners. So, for example, our guide would tell us that the French tried to restore parts of the great monuments but they used cement to do it. “A terrible mistake.” Then, the Indian Buddhists tried to clean the limestone used in the construction with acid. This, of course, further eroded the precious carvings. “The Indians did not know what they were doing.” Now, the Germans are involved, attempting to restore and keep the buildings from further dilapidation with glue. “We shall see if they are successful!”

The other great asset is the ancient monuments of Angkor that bring around two million visitors per annum into the country. These monuments represent the golden age of Cambodia when the Khmer Empire was the most powerful in Southeast Asia. But these monuments have been allowed to fall into ruin and disrepair. Most recently they have been the target of destruction by the Khmer Rouge of Pol Pot despite Brother Number One using them as the reason to look upon the future with optimism, declaring, ‘If we can build Angkor, we can do anything’. Interestingly, a corollary of the idea of Angkor is that anything that goes wrong can be blamed on foreigners. So, for example, our guide would tell us that the French tried to restore parts of the great monuments but they used cement to do it. “A terrible mistake.” Then, the Indian Buddhists tried to clean the limestone used in the construction with acid. This, of course, further eroded the precious carvings. “The Indians did not know what they were doing.” Now, the Germans are involved, attempting to restore and keep the buildings from further dilapidation with glue. “We shall see if they are successful!”

“Why don’t you carry out any of the restoration yourselves?” I ask.

The response is a sheepish smile. The truth is that the government spends nothing on its ancient monuments, preferring to rely upon the goodwill and charity of other nations. At the moment, it is the Germans, Indians, Japanese and Koreans who are involved, providing funds and expertise.

The same goes for the clearance of land mines. Between them, the Americans and the Khmer Rouge managed to plant millions of anti personnel mines all over the country. Today, some 30 years on, it is estimated that there are still between 3 and 6 million land mines active and undiscovered around the countryside. There are whole areas that we are advised to avoid and rural people (at a rate of about 40 people each year) are still being injured or killed by accidentally stepping on one of these dreadful weapons. It could be imagined that land mine clearance would be the number one priority of the army but, in fact, it is being carried out by the British, Canadians, Koreans and Australians.

However, it is to see the magnificent ancient monuments that draws us to Cambodia and brings us to the town of Siem Reap. It is a charming town with a distinctly French influence in its buildings and tree lined boulevards. The Stung Siem Reap (river) flows slowly through the centre and into Tonle Sap, or Great Lake, which was the richest freshwater fishing ground in the world. At the moment, it is almost empty, partly because it is the end of the dry season and it has yet to be replenished by rain and the rising waters of the Mekong River, but, mostly, because the Chinese have diverted the Mekong for their own purposes (electricity and water), with no regard for the effect it has on those downstream.

Despite the fact that some 2 million people now visit the ancient monuments around Siem Reap, the rural people are among the poorest in Cambodia. We were joined on our journey by Daniel and Camilla (Dan’s girlfriend) who have both recently completed their university studies and are soon to embark on the real world of work and responsibility. It was wonderful to see them and to see them looking so well and relaxed after the stress of final examinations. It gave us a chance to catch up and discuss their plans for the future as well as hear tales of those back home – something we have missed during our exploration.

Despite the fact that some 2 million people now visit the ancient monuments around Siem Reap, the rural people are among the poorest in Cambodia. We were joined on our journey by Daniel and Camilla (Dan’s girlfriend) who have both recently completed their university studies and are soon to embark on the real world of work and responsibility. It was wonderful to see them and to see them looking so well and relaxed after the stress of final examinations. It gave us a chance to catch up and discuss their plans for the future as well as hear tales of those back home – something we have missed during our exploration.

Our first visit was to Angkor Wat, the largest religious structure in the world. It was built sometime in the 12th century as a Hindu centre for the worship and learning of the deity Vishnu by Suryavarman II but, later transformed into a Buddhist temple by his successors. It was completed around the same time as the European gothic cathedrals of Notre Dame and Chartres.

Our first visit was to Angkor Wat, the largest religious structure in the world. It was built sometime in the 12th century as a Hindu centre for the worship and learning of the deity Vishnu by Suryavarman II but, later transformed into a Buddhist temple by his successors. It was completed around the same time as the European gothic cathedrals of Notre Dame and Chartres.

Built from sandstone blocks, Angkor Wat replicates the spatial universe in miniature. The central tower is Mount Meru with its surrounding smaller peaks, bounded in turn by continents (represented by lower courtyards) and the ocean (represented by the moat). The access across the 200 metre-wide moat is via a symbolic rainbow bridge that enables humans to reach the abode of the gods. The whole area takes up over one square kilometer of grounds and the summit of the temple at 63 metres dominates the flat forest area that encompasses the temple. The significance of Angkor Wat to Cambodia cannot be understated; it is a source of great national pride, it is the epicentre of the Khmer Kingdom and appears in the middle of the national flag.

Built from sandstone blocks, Angkor Wat replicates the spatial universe in miniature. The central tower is Mount Meru with its surrounding smaller peaks, bounded in turn by continents (represented by lower courtyards) and the ocean (represented by the moat). The access across the 200 metre-wide moat is via a symbolic rainbow bridge that enables humans to reach the abode of the gods. The whole area takes up over one square kilometer of grounds and the summit of the temple at 63 metres dominates the flat forest area that encompasses the temple. The significance of Angkor Wat to Cambodia cannot be understated; it is a source of great national pride, it is the epicentre of the Khmer Kingdom and appears in the middle of the national flag.

The first sight of the great temple is awe inspiring. Crossing the moat, the surrounding walls are ornately and meticulously carved into thousands of nymphs who serve Lord Vishnu. It seems, every other available bit of stone is delicately carved by expert stonemasons into patterns that are sometimes simple and often complicated. The doorways, of which there are 5 (one for the King, one for high priests, one for pilgrims, including royals and two for elephants), are carved with sandskrit on their inner faces. But this is just the foretaste. Emerging through the outer wall, we come to a vast green area divided by a long pathway that leads to the temple itself. On either side of the path are imposing libraries and between them and the temple are two lakes used for bathing prior to worship. Originally, this whole area would be a beautiful, lush, tropical garden that flashed colour and scent, giving the pilgrim a feeling of trespassing into an ethereal world occupied by gods.

The first sight of the great temple is awe inspiring. Crossing the moat, the surrounding walls are ornately and meticulously carved into thousands of nymphs who serve Lord Vishnu. It seems, every other available bit of stone is delicately carved by expert stonemasons into patterns that are sometimes simple and often complicated. The doorways, of which there are 5 (one for the King, one for high priests, one for pilgrims, including royals and two for elephants), are carved with sandskrit on their inner faces. But this is just the foretaste. Emerging through the outer wall, we come to a vast green area divided by a long pathway that leads to the temple itself. On either side of the path are imposing libraries and between them and the temple are two lakes used for bathing prior to worship. Originally, this whole area would be a beautiful, lush, tropical garden that flashed colour and scent, giving the pilgrim a feeling of trespassing into an ethereal world occupied by gods.

The entrance to the temple itself is via steep steps that take us from earth, up toward heaven. The journey continues through a gallery of murals depicting great stories from the past, through further bathing areas and up to the area at the bottom of the temple ‘spire’. There are another two small libraries before the (very) steep climb to the highest point that represents Mount Meru. All through the temple are statues of various Buddha deities, especially of the goddess Lakshmi who is the partner of Vishnu and chief of the numerous apsara nymphs that adorn the walled areas.

The construction is stunning, the craftsmanship outstanding and the impact of the structure leaves an indelible image in the memory. It does not simply represent a place of (originally) Hindu worship but, more importantly, it represents the power, wealth and artistry of people that dominated the area over 1,000 years ago.

The construction is stunning, the craftsmanship outstanding and the impact of the structure leaves an indelible image in the memory. It does not simply represent a place of (originally) Hindu worship but, more importantly, it represents the power, wealth and artistry of people that dominated the area over 1,000 years ago.

More impressive in many ways is the fortified city of Angkor Thom (Great City). It is 10 square kilometers in size and, at its height, boasted a population of one million people at a time when London was a scrawny town of 50,000 inhabitants. It was built by King Jayavaraman VII, some 50 years after the completion of Angkor Wat, in the style of the Buddhist faith. The inhabitants lived in wooden houses because the right to live in brick and stone was reserved for the gods. The wooden buildings decayed long ago, leaving the skeleton of extravagantly beautiful religious structures.

The bridge across the moat is decorated with two seven headed snakes that protect the land from the underworld of demons. The snakes, that run the length of the bridge like railings, are held by numerous gods of the causeway who look as if they are involved in a tug of war against the snakes.

The bridge across the moat is decorated with two seven headed snakes that protect the land from the underworld of demons. The snakes, that run the length of the bridge like railings, are held by numerous gods of the causeway who look as if they are involved in a tug of war against the snakes.

The main entrance (lying to the South) is an imposing structure, large enough for elephant to pass, topped by four gargantuan faces of Avalokiteshvara (the Bodhisattva of Compassion) facing each of the cardinal directions. Inside the gate is an enormous grass area where the people dwelt and, in the centre of everything, stands the great Buddhist temple of The Banyon.

The main entrance (lying to the South) is an imposing structure, large enough for elephant to pass, topped by four gargantuan faces of Avalokiteshvara (the Bodhisattva of Compassion) facing each of the cardinal directions. Inside the gate is an enormous grass area where the people dwelt and, in the centre of everything, stands the great Buddhist temple of The Banyon.

It has 54 Gothic-like towers decorated with 216 large, coldly smiling faces of Avalokiteshvara that, reputedly, bear a strong resemblance to King Jayavaraman himself. These huge visages glare down from every angle watching over his vast empire and serve to remind all subjects who is in charge. The walls are richly decorated with murals that vividly depict everyday life in 12th Century Cambodia.

It has 54 Gothic-like towers decorated with 216 large, coldly smiling faces of Avalokiteshvara that, reputedly, bear a strong resemblance to King Jayavaraman himself. These huge visages glare down from every angle watching over his vast empire and serve to remind all subjects who is in charge. The walls are richly decorated with murals that vividly depict everyday life in 12th Century Cambodia.

Standing slightly aside from the temple is the Terrace of the Elephants, a giant viewing platform for public ceremonies and games. Watched by the god-king who would be flanked by mandarins and handmaidens, this would be the place where the power and pomp of the Khmer Empire would have been on display with infantry, cavalry, chariots and elephants parading across the grass central area in a colourful procession of pennants and standards.

As the star of the Angkor Empire dimmed following the silting of the irrigation network and two long periods of drought (global warming obviously!), the Thais gained the ascendency. They sacked the city twice and made off with thousands of intellectuals, artisans and dancers from the royal court whose profound impact on Thai culture is still in evidence today.

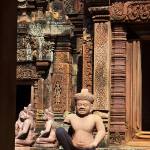

Around the two dominant temples of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom are, seemingly, hundreds of others that pop up out of the countryside wherever we turn. The Angkorian era started in AD 802 and just about every king seems to have built at least one temple during his reign. We visited five others that were built in different styles and with different materials depending upon the time when they were constructed. The early ones were built from red clay brick and have close similarities to the temples built by the Charma people of My Son in Vietnam that we saw a couple of weeks previously. These constructions are more like 1200 years old and are crumbling (there is only so much restoration a foreigner can do!). The most interesting of these old temples is Banteay Srei which some scholars consider to be the crown jewel of Angkorian art. Begun in AD 967, it is built from pink stone and is full of fine, delicate stone carving that is stunning in its intricate detail. The doorways are all tiny, small enough for Debbie to have to bow her head to pass, and, it is claimed, that the small and beautiful complex was built for women.

Around the two dominant temples of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom are, seemingly, hundreds of others that pop up out of the countryside wherever we turn. The Angkorian era started in AD 802 and just about every king seems to have built at least one temple during his reign. We visited five others that were built in different styles and with different materials depending upon the time when they were constructed. The early ones were built from red clay brick and have close similarities to the temples built by the Charma people of My Son in Vietnam that we saw a couple of weeks previously. These constructions are more like 1200 years old and are crumbling (there is only so much restoration a foreigner can do!). The most interesting of these old temples is Banteay Srei which some scholars consider to be the crown jewel of Angkorian art. Begun in AD 967, it is built from pink stone and is full of fine, delicate stone carving that is stunning in its intricate detail. The doorways are all tiny, small enough for Debbie to have to bow her head to pass, and, it is claimed, that the small and beautiful complex was built for women.

The other temple of note was called Ta Prohm which was, apparently, used to film Tomb Raider. Here, the jungle has taken over despite the restoration efforts of the Indians. The crumbling walls and towers are locked in the muscular, python-like grip of centuries old strangler vine, the roots of which twist and turn and delve into the stone construction like virus.

The other temple of note was called Ta Prohm which was, apparently, used to film Tomb Raider. Here, the jungle has taken over despite the restoration efforts of the Indians. The crumbling walls and towers are locked in the muscular, python-like grip of centuries old strangler vine, the roots of which twist and turn and delve into the stone construction like virus.

I imagine that, like a 1970s Fiat car whose bodywork is so rusted that it is held together only by paint, if the vines were removed, the whole temple would collapse. Those parts of the temple not gripped by vine are infested with moss, creeping plant and shrubs that sprout from the roofs of grand porches. Many of the corridors are impassable, being clogged with fallen stone. Jumbled piles of delicately carved blocks of sandstone are scattered around in heaps that look as if they have been swept into place by servants of the gods. Lara Croft must have loved it here.

I imagine that, like a 1970s Fiat car whose bodywork is so rusted that it is held together only by paint, if the vines were removed, the whole temple would collapse. Those parts of the temple not gripped by vine are infested with moss, creeping plant and shrubs that sprout from the roofs of grand porches. Many of the corridors are impassable, being clogged with fallen stone. Jumbled piles of delicately carved blocks of sandstone are scattered around in heaps that look as if they have been swept into place by servants of the gods. Lara Croft must have loved it here.

In contrast to the temples of the rich, the countryside is home to the poor, agrarian people who still have to scratch a living from the earth. The tarmac roads soon give way to the rutted surface of baked, red soil and the mortar and brick houses become huts thrown together from wood and palm leaves and/or corrugated iron. There is no telephone, electricity or running water. Sewerage is a hole in the ground. What water there is has to be drawn from the earth by hand pump and boiled; what power there is comes from batteries that are recharged every couple of days from generators. I worked out that for a small house to run battery power for a year would cost US$200, a sum not many would be able to afford.

In contrast to the temples of the rich, the countryside is home to the poor, agrarian people who still have to scratch a living from the earth. The tarmac roads soon give way to the rutted surface of baked, red soil and the mortar and brick houses become huts thrown together from wood and palm leaves and/or corrugated iron. There is no telephone, electricity or running water. Sewerage is a hole in the ground. What water there is has to be drawn from the earth by hand pump and boiled; what power there is comes from batteries that are recharged every couple of days from generators. I worked out that for a small house to run battery power for a year would cost US$200, a sum not many would be able to afford.

Work is provided by duck farming (for eggs mostly) and small rice fields that stretch across the flat land for miles. Water is scarce at this time of year and much of the farming is for dry rice that has a poor yield. A good yield of wet sticky rice provides the highest sale value at US$250 per ton and a farmer needs around a hectare (two and a half acres) of land to produce this much crop. After expenses, there isn’t much left. It’s a hard existence of back breaking manual work and it is difficult to see how a family could break out of the cycle of poverty.

Away from the flat farmlands, the countryside is bordered by some small hills amongst one of which is to be found Khal Spean that is referred to in English as ‘The River of a Thousand Lingas’. It is a carved riverbed set deep in the green hillside jungle requiring a short, hot hike up 1,500 metres to reach the beginning of the carvings. The Angkorians believed that the river that flowed over the carvings of male and female symbols of fertility became holy water and to bathe the face or body in this water would wash away sin.

Away from the flat farmlands, the countryside is bordered by some small hills amongst one of which is to be found Khal Spean that is referred to in English as ‘The River of a Thousand Lingas’. It is a carved riverbed set deep in the green hillside jungle requiring a short, hot hike up 1,500 metres to reach the beginning of the carvings. The Angkorians believed that the river that flowed over the carvings of male and female symbols of fertility became holy water and to bathe the face or body in this water would wash away sin.

The rock on the river bank was carved with images of the god Vishnu and his consort Laksmei, the rock on the river floor were continuously carved with forms of male and female fertility, the water coursing first over the male and then into the female forms. The river flowed in a dry season trickle, making the symbols easy to see and to follow over a series of waterfalls as it descended the hill onto the plain below. Debbie was the embodiment of a water nymph, turning into the living representation of Laksmei herself being cleansed by the holy water. I simply enjoyed standing under a waterfall, allowing the cool, clear water to massage my follicles and wash away my (considerable) sins.

The rock on the river bank was carved with images of the god Vishnu and his consort Laksmei, the rock on the river floor were continuously carved with forms of male and female fertility, the water coursing first over the male and then into the female forms. The river flowed in a dry season trickle, making the symbols easy to see and to follow over a series of waterfalls as it descended the hill onto the plain below. Debbie was the embodiment of a water nymph, turning into the living representation of Laksmei herself being cleansed by the holy water. I simply enjoyed standing under a waterfall, allowing the cool, clear water to massage my follicles and wash away my (considerable) sins.

As a contrast to the history of ancient Angkor, we could not avoid visiting the Land Mine Museum and Killing Fields of modern Cambodia. People talk openly about the Khmer Rouge but they prefer to refer to the time, rather quaintly, as the civil war. The Khmer Rouge rose to power, sponsored by the Chinese and Thai governments, towards the end of the Vietnamese war with the US. Led by Saloth Sar who called himself Pol Pot or Brother Number One, about 2 million Cambodians died (1 in 8 of the population) during a four year period in one of the bloodiest and inept pieces of social engineering the world has ever experienced.

The number of casualties and their enormity are almost impossible to understand. The regime abolished money, forcefully evacuated cities, prohibited religious practices, suspended education, newspapers and postal services, collectivized eating and made everyone wear peasant clothing. Its economic plan called for average national yields of rice that were more than twice as high as those in the most productive areas of Cambodia (now known as Kampuchea). The regime proposed a class war to turn the economy around by abolishing class distinctions, destroying pre-revolutionary institutions and transforming the population into unpaid agricultural workers. In May 1975, a government spokesman proudly announced that “more than two thousand years of Cambodian history had ended.” This was now Year Zero.

What rice was produced was used by the Khmer Rouge to buy weapons so that the population was forced to work for 12-15 hours a day on meals that consisted of little more than watery rice porridge. Disease stalked the work camps, malaria and dysentery struck down whole families. Disobedience of any sort brought immediate execution. Anyone considered to be a monk or an intellectual was shot – having glasses was reason enough to be killed. The regime soon began devouring anyone seen as insufficiently doctrinaire – entire cadres of people and all their relatives.

Khmer Rouge rule was brought to an end after they undertook an invasion of Vietnam which responded in force. The Rouge had neither the resources nor the manpower to win such a conflict and the near empty capital of Phnom Penh was liberated in early 1979.

The bones of the dead can now be seen in a number of impersonal displays all over the country but the land mines that the Khmer Rouge planted in an effort to halt the advancing Vietnamese are still being deactivated. There are still between 3 and 6 million of them buried and undiscovered. Although the areas around major towns and cities are considered safe, mines continue to claim the lives and limbs of the population today.

To their credit, the people of Cambodia have bounced back from these atrocities and they are an optimistic, cheerful and hospitable lot. It is a pleasure to travel in their country and to experience their culture and their way of life. However, they acknowledge that they continue to be ill served by a government that seems to be wholly detached from those they are suppose to serve. But, in typical Cambodian style, they shrug their shoulders and hope for the best.

No comments yet.