I’m not sure what possessed me to book a climb up to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro (5,895 metres/ 19,200 feet) but I suppose I thought it was a good idea at the time and something Debbie would enjoy. As we trudged our way to the summit, in the dark early hours of the morning, with my lungs struggling for air, feeling nauseous and having to concentrate hard due to a diminishing feeling of balance (an effect of altitude sickness); I wished we were on a beach somewhere. Or anywhere else for that matter.

Mount Kilimanjaro is the highest peak in Africa and one of the continent’s most magnificent sights. From cultivated farmlands on the lower levels, brimming with maize and millet, the mountain rises through lush rainforest, the boughs of trees clothed in abundant epiphytic lichen, orchids and moss, through alpine meadows dotted with clumps of yellow and purple flowers, through a barren lunar landscape of dust, dust and rock to the peak of Uhuru.

Mount Kilimanjaro is the highest peak in Africa and one of the continent’s most magnificent sights. From cultivated farmlands on the lower levels, brimming with maize and millet, the mountain rises through lush rainforest, the boughs of trees clothed in abundant epiphytic lichen, orchids and moss, through alpine meadows dotted with clumps of yellow and purple flowers, through a barren lunar landscape of dust, dust and rock to the peak of Uhuru.

The geological origin of ‘Kili’, as known by the locals, is part of the Rift Valley dating back about one and a half million years ago to the early Pleistocene period. It is the tallest stand alone mountain in the world. The Kibo peak area last erupted 100,00 years ago but it remains a dormant active volcano and a slight smell of sulphur reminds us that we are treading on the top of earth’s unpredictable emotions.

Interestingly, the origin of the name Kilimanjaro is unclear. In Kiswahili the word ‘Kilima’ means small hill while ‘Najaro’ means greatness. According to ancient myths Njaro is also the name of a fearful demon who was living on the summit. To confuse matters further, to the Waswahili people, drivers of caravans for centuries, the name Kilimanjaro meant landmark. But confusion is Africa’s middle name and a simple explanation is simply not in its nature.

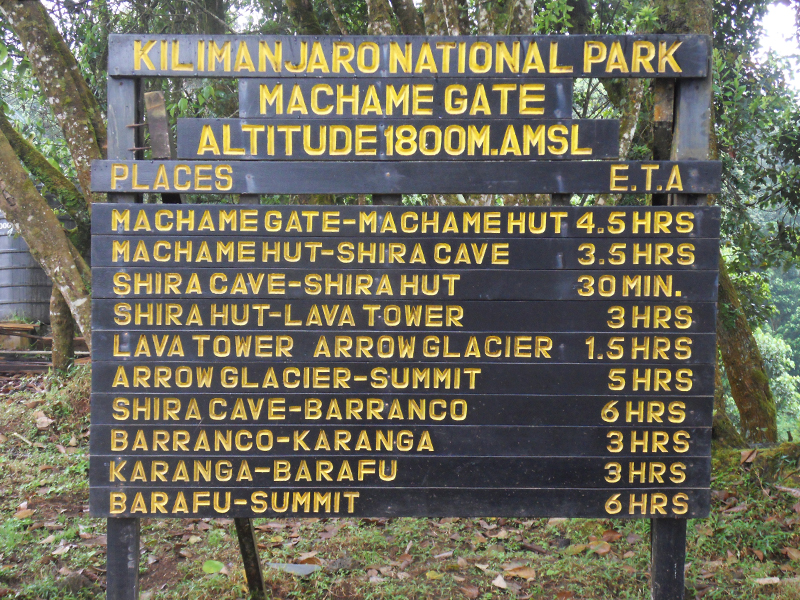

We went up the Machame Route on a seven day, six night trek that I thought would aid acclimatisation and would also avoid the crowded Marangu Route known locally as the ‘coca cola’ route for being the easiest and most popular trail.

The first day began at the Machame Gate, a helpful 1,678 metres high, where organised chaos reigned as permits were bought, porters were recruited and trekkers made their final preparations. It takes well over an hour for our party to assemble in some sort of order and introductions made. For the two of us, we have one guide, one assistant guide, a camp manager, a cook and sixteen porters! It’s good to know that we are kick starting the Tanzanian economy. Each porter has their packs checked for weight before they are allowed to start; the total weight (including their own kit) cannot exceed 20 Kgs. It seems to me that somehow the organisers manage to get around this restriction as the crew look to be carrying much more weight than they should.

The first day began at the Machame Gate, a helpful 1,678 metres high, where organised chaos reigned as permits were bought, porters were recruited and trekkers made their final preparations. It takes well over an hour for our party to assemble in some sort of order and introductions made. For the two of us, we have one guide, one assistant guide, a camp manager, a cook and sixteen porters! It’s good to know that we are kick starting the Tanzanian economy. Each porter has their packs checked for weight before they are allowed to start; the total weight (including their own kit) cannot exceed 20 Kgs. It seems to me that somehow the organisers manage to get around this restriction as the crew look to be carrying much more weight than they should.

The first day’s climb took us through the rainforest. The track was narrow and very muddy. Mist hung over the trees and a light rain moistened the air. It was very quiet; it was as if all the bird and animal life had been chased away by the demon of the mountain to leave an eerie silence. Creepers wound their way up and along the trees, moss – Spanish Beard – hung down from the branches like green hair and lichen stuck to every available surface.

The first day’s climb took us through the rainforest. The track was narrow and very muddy. Mist hung over the trees and a light rain moistened the air. It was very quiet; it was as if all the bird and animal life had been chased away by the demon of the mountain to leave an eerie silence. Creepers wound their way up and along the trees, moss – Spanish Beard – hung down from the branches like green hair and lichen stuck to every available surface.

We made camp at 3,039 metres (9,900 feet) after an ascent of 18 km near the edge of the forest but still enveloped within it. The day’s walk had been easy, lasting a little over 4 hours and we had taken it very slowly. “Pole pole”, Swahili for slowly slowly, the guide Charles kept repeating. Charles is a local of average height. A quiet, lovely chap of few words. His understanding of English isn’t brilliant and we have to ask the same question in several different ways before, we think, we get the answer. The assistant guide, Jackson, has a better command of English but we still have to be careful not to create misunderstandings. Part of the difficulty is that the translation from Swahili to English is not often direct and involves a different thought process.

The following morning, we were up early (0630 am) in the misty murkiness of the damp, muddy rainforest. I was beginning to feel concerned that we would be spending the next 5 days in cloud, seeing nothing, but around midday my grumpiness was dismissed as we emerged from the top of the mists into brilliant sunshine and immediately had a fantastic view of the peak of Kilimanjaro, 2,000 metres above us.

Having made it to camp (3,850 metres/ 12,500 feet) by 1.00pm and having already stopped for lunch, we were taken off on a ‘walk’ in the afternoon. The supposed aim was to help our acclimatisation but it felt more like trying to fill the time. This became a daily ritual and, I became convinced, that Charles had to follow the company formula of going from camp one to camp two to camp three and stopping no matter how quickly the clients cover the distance. Even at ‘pole pole’ pace we never walked for more than 4 hours between camps and I am sure we could have saved a day without any problem and without spending long hours in our tent reading.

Camp Two, at a place called Shira, became very cold during the night as the sky cleared. When I need to get up for a pee (an inevitability given that we are made to drink at least 4 litres of water a day to combat dehydration and altitude sickness), it takes a good 30 minutes to get up the courage to crawl out of a warm sleeping bag, get dressed and venture out into the freezing air. In fact, the first thoughts I have are

Camp Two, at a place called Shira, became very cold during the night as the sky cleared. When I need to get up for a pee (an inevitability given that we are made to drink at least 4 litres of water a day to combat dehydration and altitude sickness), it takes a good 30 minutes to get up the courage to crawl out of a warm sleeping bag, get dressed and venture out into the freezing air. In fact, the first thoughts I have are

“do I really need to have a pee?”

“Can I last until morning?”

A glance at my watch tells me the answer is no. It’s only 11.00pm and first light is around 0630, seven and a half hours away. I then have to find my clothes in the dark, hopefully without waking Debbie. Of course, the clothes are cold. Then I want to escape the tent without waking everyone else and, if I do, I hope they are too polite to cry out, “We know what you’re doing!” It is all a bit of an ordeal but one that gets easier the more often I do it. It turns out that Debbie sleeps with her clothes, needed the next day, to keep them warm!

Day Three begins with a frozen tent. The zip is frozen too and it is some time before we fight our way out into the crisp air. The views are wonderful. Fluffy white cloud stretches away as far as the eye can see and I wonder how good it would feel to lie down in the comfort of the clean quilt of its soft blanket. Nearby the peak of Mount Meru penetrates through the whiteness like a broken elbow.

Day three took up through the so called Alpine Meadow. Not that there is much grass around – just odd clumps of the stuff spaced around the rock, shale and dust. There are some oddly unique plants surviving in this semi desert: A funny type of lobelia that grows up to 3 metres high and looks more like a cactus with leaves sprouting from its base. The other is called Senecio Kilimanjari and is the upside down version of the lobelia. Both have learnt to live in the dry, cold atmosphere of the southern side of the mountain.

Day three took up through the so called Alpine Meadow. Not that there is much grass around – just odd clumps of the stuff spaced around the rock, shale and dust. There are some oddly unique plants surviving in this semi desert: A funny type of lobelia that grows up to 3 metres high and looks more like a cactus with leaves sprouting from its base. The other is called Senecio Kilimanjari and is the upside down version of the lobelia. Both have learnt to live in the dry, cold atmosphere of the southern side of the mountain.

We reached a height of 4,650 metres (15,100 feet) at a Lava Tower (where some so and so Germans refused to get out of our photos) before descending again, through the rain, to Barranco Camp at 3,982 metres (12,950 feet). The rain wasn’t welcome, nor was the afternoon ‘acclimatisation’ walk, especially as everything froze solid overnight when the sky cleared.

So Day four began with ice everywhere and another fight to get out of the tent. Although our outer clothing was still wet from the day before, the sun, aided by the dry atmosphere, soon dried things off. The trail had us scrambling over rock and tip toeing along ledges, hugging the mountain side like it was our best friend. Charles told us that many people take the opportunity to kiss the rock at this point but we declined not knowing where other peoples’ mouths may have been.

We finished at Karanga Camp (4,064 metres/ 13,200 feet). After another ‘aclimatisation’ walk, the clouds below us began to part and, for the first time, we could see the countryside around the base of the mountain. The yellow fields of Maize appeared like a carpet covering most of the ground with the small town of Moshi smack in the middle. It seemed very inviting, particularly the thought of a shower together with a thorough body scrub. We were managing to wash using one small bowl of water each per day and, whilst Debbie still smelt like an angel, I am sure I did not.

We finished at Karanga Camp (4,064 metres/ 13,200 feet). After another ‘aclimatisation’ walk, the clouds below us began to part and, for the first time, we could see the countryside around the base of the mountain. The yellow fields of Maize appeared like a carpet covering most of the ground with the small town of Moshi smack in the middle. It seemed very inviting, particularly the thought of a shower together with a thorough body scrub. We were managing to wash using one small bowl of water each per day and, whilst Debbie still smelt like an angel, I am sure I did not.

Day five took us to Barafu Camp (4,650 metres/ 15,100 feet) from which we would make our bid for the summit. We were allowed a lie in until 7.00 am so that those at the base camp could clear off before we arrived. It was another easy walk, ‘pole pole’, through the high desert where nothing grows and the landscape is full of dark rock and slippery shale and yet more dust.

We had wonderful views of the Mawenzi peaks of Kilimanjaro away to the east. They stood proud, black and defiant, inaccessible to all but the most accomplished mountaineers. The three peaks are not as high as Uhuru atop the Kibo icefields that we are going to attempt. Fortunately.

By now, we had several talks with Charles as to how long it would take us to reach the summit. We were concerned that we would get there too quickly, arriving before dawn. He kept assuring us that we should leave at midnight (as the company stipulates) and there would be no problem. We also had much discussion about what and how much clothing we should wear. “As much as possible” seemed rather vague. As a rule of thumb, the temperature drops by one degree Celsius for every 200 metres climbed. So 6,000 metres would be about 30 degrees colder than sea level. This only gave us a vague idea that it would be minus something at the peak. But what of the wind-chill? No one had any idea.

So we got dressed at 11pm wearing 3 layers on our legs and five on our bodies. Two hats, two pairs of gloves, Debbie – two pairs of socks, me – one. We packed an extra thick top to wear on the summit, took 3 litres of water each, some chocolate, our head torches and cameras. What could go wrong?

We set off at midnight and immediately found ourselves at the back of a great single file queue of people meandering their way upwards. This seemed liked torture at first but, within an hour, we had passed them all and were putting steadily greater distances between us and the next climbers.

We were still going milimetrically slowly: ‘pole pole’ – each step being about one boot length at a time. It wasn’t hard on the muscles but it became increasingly harder on our bodies. At this slow pace, I was finding it difficult to get my breathing into a rhythm which made it much harder on my lungs. I felt as if I was only using half capacity and breathing twice as fast as a result, but I simply couldn’t manage to get the regular, slow, deep breathing that I had managed at altitude previously.

I also felt sick which is a not uncommon altitude problem. Later on, I began to lose my sense of balance; it was fine whilst I concentrated on the small pool of light in front of me illuminated by my torch, but if I looked up or around me, I started wobbling all over the place. I know some will feel this is perfectly normal for me, so let’s say it was much worse than usual. In contrast, Debbie was bouncing along, full of the joys of spring, making it all look easy. She had suffered headaches in the days leading up to the final ascent but was now perfectly fine except for being slightly short of breath in the oxygen depleted air.

We both found it a grind. It was continuously, relentlessly uphill for hour after hour in the pitch darkness with only the sound of our rasping breath breaking the silence. Mercifully, the mountain shale beneath our feet had frozen solid making the going easier than it might have been. Occasionally, I would call for a stop to try to regain control of my breathing but the cold limited such breaks to no more than two minutes.

Sometime around 4.00am Charles stopped and told us that we would reach the summit well before sunrise. If I had had the strength, I would have killed him! After all this gigantic effort, our reward would be to stand on the top of Africa in complete darkness. What a complete plonker! To have arrived an hour late would have been infinitely preferable and to think we had tried to talk about this several times but to no avail was even more galling.

Now there was nothing to be done except swallow our situation and plod on. We reached Stella Point (5,650 metres/ 18,400 feet) around 0430 where the climb flattens out at the top of the mountain. We stopped for a cup of tepid water from a thermos (all our other water having now frozen) and put on our last layer of clothing. The summit was only another 200 metres or so above us but it was another hour’s walk to get there.

Thus it was at 0530 on the morning of Saturday 14th August, we stood on the African Continent’s highest summit (5,895 metres / 19,200 feet) and saw….nothing! Thank goodness for flash photography! We had taken the batteries out of our cameras and secreted them about our underwear to keep them warm. Now, out in the cold of -20c plus the wind-chill they lasted about 10 minutes before they gave up the ghost and the cameras froze anyway. The only good news was, that as we were the first to the top, there was no one else (stupid enough to be) around to get in the way of our photos! It was too cold to remain at the top to await sunrise and, by now, all our fingers had gone numb (I’m still missing the feeling in the tips of four fingers a week later).

Thus it was at 0530 on the morning of Saturday 14th August, we stood on the African Continent’s highest summit (5,895 metres / 19,200 feet) and saw….nothing! Thank goodness for flash photography! We had taken the batteries out of our cameras and secreted them about our underwear to keep them warm. Now, out in the cold of -20c plus the wind-chill they lasted about 10 minutes before they gave up the ghost and the cameras froze anyway. The only good news was, that as we were the first to the top, there was no one else (stupid enough to be) around to get in the way of our photos! It was too cold to remain at the top to await sunrise and, by now, all our fingers had gone numb (I’m still missing the feeling in the tips of four fingers a week later).

So we trudged back to Stella Point slowly, watching the dirty orange glow of dawn spread across the sky and gradually brighten until the top of a rosy sun peered above the horizon. I now wish that I had told our guide to wander around the summit for an hour to await the sunrise or, having got to Stella Point, to have ordered him back to the top. But hindsight is a wonderful thing and my logical thought process must have frozen with the rest of my body. It’s something I regret and annoys me every time I think of it.

So we trudged back to Stella Point slowly, watching the dirty orange glow of dawn spread across the sky and gradually brighten until the top of a rosy sun peered above the horizon. I now wish that I had told our guide to wander around the summit for an hour to await the sunrise or, having got to Stella Point, to have ordered him back to the top. But hindsight is a wonderful thing and my logical thought process must have frozen with the rest of my body. It’s something I regret and annoys me every time I think of it.

From Stella Point it was a slide down the now loose shale back to camp, stopping off regularly to shed clothes. We were back by 0830 and allowed a couple of hours rest before a quick brunch (I couldn’t eat as I still felt sick) and then continued down for a further 3 hours to reach Mweka Camp at 3,077 metres where we stopped for the night. It had been a long day, walking for nearly 12 hours, without sleep, about 4,000 feet up and 10,000 feet down again. My knees suffered on the way down; the constant jarring eventually causing considerable swelling, especially to the right knee which still hasn’t recovered from falling off a bike in Vietnam at least six weeks ago. It’s somewhat ironic that I would much rather climb up than down as it’s much easier on the joints.

The final morning, after a lecture to the guide over breakfast concerning his stupidity at getting us to the peak too early, we set off for a three hour trek back down the muddy trail of the rainforest to Mweka Gate. There we enjoyed a well earned bottle of ‘champagne’ (excellent Flexinet Cava). After long goodbyes to the crew who had looked after us so well, we returned to the sanctuary of a nearby hotel where we washed our bodies three times in hot, wonderful water to be rid of the mud, dust, sweat and grime of the last week.

The final morning, after a lecture to the guide over breakfast concerning his stupidity at getting us to the peak too early, we set off for a three hour trek back down the muddy trail of the rainforest to Mweka Gate. There we enjoyed a well earned bottle of ‘champagne’ (excellent Flexinet Cava). After long goodbyes to the crew who had looked after us so well, we returned to the sanctuary of a nearby hotel where we washed our bodies three times in hot, wonderful water to be rid of the mud, dust, sweat and grime of the last week.

Despite the appalling timing of our ascent, we still enjoyed the trek. The wonderful views, the changing climate, the glorious sense of freedom that you only get in the mountains, the crystal clear air (dust allowing), the wonderful feeling of being on top of the world with the earth at our feet; these are experiences that we will never forget. Would we encourage others to do it? Definitely. Would we do it again? No chance!

No comments yet.