Jaipur is mostly pink. A result of an edict issued by Maharaja Ram Singh in 1876 to commemorate the forthcoming visit of The Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). The owners of the city’s buildings are required to repaint the outside of their dwellings every two years with another coat of pink paint but, if they do, they must use an unusually rare concoction that looks 5 years old as soon as it is applied.

We arrived in the capital of Rajasthan on the overnight train from Jaisalmer at 5.00am, feeling dead on our feet, stumbling over sleeping bodies all over the pavements. We have travelled around the region by train and I could not work out why we should have felt so tired. It wasn’t the fact that the train was not weatherproof, as the evening’s monsoon rain worked its way through the roof and down the walls and window. It wasn’t that it was any more or less comfortable than other train journeys

We arrived in the capital of Rajasthan on the overnight train from Jaisalmer at 5.00am, feeling dead on our feet, stumbling over sleeping bodies all over the pavements. We have travelled around the region by train and I could not work out why we should have felt so tired. It wasn’t the fact that the train was not weatherproof, as the evening’s monsoon rain worked its way through the roof and down the walls and window. It wasn’t that it was any more or less comfortable than other train journeys

The only thing that I could think of was that the compartment’s air conditioning was set to freezing and, despite shutting it off, it refused to give up, blowing through all the cracks in the roof and spitting rain everywhere. So we both had headaches and our bodies felt like we had been abducted by aliens and used for inappropriate experiments.

Nonetheless, after a couple of hours extra sleep, we set off to explore the city. Jaipur is not that old, having been started in 1727 by the great warrior-scholar Jai Singh who named the city after himself. It was Northern India’s first planned city and was laid out according to strict principles set down in the Shipla Shastra, an ancient Hindu treatise on architecture. At the centre of a grid system is the city palace complex, containing the palace itself, the administrative quarters, the remarkable Jantar Mantar (the observatory) and the Zenana Mahals (women’s palaces). Avenues divide the Pink City into neat rectangles, each specialising in a particular trade, as specified in the Shipla Shastra. It’s all arranged in a very orderly fashion and minimises our chances of getting lost.

The long, wide avenues are filled with endless rows of little shops, all uniform in size. According to the original plan, most shops of a similar type are clumped together so that the pressure of the competition from next door keeps the shop owners on their toes. It also keeps them in our face making the walk along the narrow pavement full of twists and turns to avoid the stuff hanging outside shops and the shopkeepers touting for business.

The sides of the road may be full of parked vehicles but it is also put to use by street vendors – fruit and veg sellers, shoe repairers, even gem traders – who clog up the most popular spots in their quest for a deal. The street corners, despite being bus stops, have barrows full of fresh produce, stalls selling Indian sweets and snacks and also serve as a general place for idle men to hang out.

The air is filled with the noise is of human endeavour: traffic, including camels and elephants, dust, rubbish and sewerage. It is busy, bustling, energetic, vibrant, hot, very hot, smelly, polluted and incredibly noisy. When the drivers lean on their horns it is impossible for us to speak to each other let alone hold a thought in our heads. But, as the poets say, “if one has not seen Jaipur, what is the point of having been born?”

The air is filled with the noise is of human endeavour: traffic, including camels and elephants, dust, rubbish and sewerage. It is busy, bustling, energetic, vibrant, hot, very hot, smelly, polluted and incredibly noisy. When the drivers lean on their horns it is impossible for us to speak to each other let alone hold a thought in our heads. But, as the poets say, “if one has not seen Jaipur, what is the point of having been born?”

Looking for some peace, we dived into the Hawa Mahal. It is the most distinctive landmark, rising five storeys straight up from street level in an eye catching pink sandstone construction that has delicate, honeycomb-screened windows. It was built to allow ladies of the royal household to watch the city streets without being observed from below. Inside there isn’t much to it; small rooms open on a large courtyard and a lovely, covered pavilion. It’s really all about the girls spending time people watching.

Looking for some peace, we dived into the Hawa Mahal. It is the most distinctive landmark, rising five storeys straight up from street level in an eye catching pink sandstone construction that has delicate, honeycomb-screened windows. It was built to allow ladies of the royal household to watch the city streets without being observed from below. Inside there isn’t much to it; small rooms open on a large courtyard and a lovely, covered pavilion. It’s really all about the girls spending time people watching.

The women would have travelled here in covered palanquins (seats carried by servants) to avoid being seen. Legend has it that the Hawa Mahal was connected to the palace by underground tunnel but, if this exists, it has yet to be discovered. It might be unearthed if the city authorities ever get round to updating the sewer and drainage facilities, as was the plan. However, they announced that they don’t have the money to spend on such essential services having decided that the construction of a flyover is more important.

The Palace itself is an appropriately enormous construction, set smack in the centre of the city. The entrance courtyard is very spacious with a Murbarak Mahal (welcome palace) standing in its centre. This is a later addition designed by Sir Swinton Jacob in a clash of styles that covers Islam, Rajput and European that now houses a museum of royal costumes and souvenirs. The most fantastic exhibit is the clothing worn by Maharaja Singh I. It is 2 metres in length, 3.5 metres round the chest and a staggering 7 metres round the waist.

The Palace itself is an appropriately enormous construction, set smack in the centre of the city. The entrance courtyard is very spacious with a Murbarak Mahal (welcome palace) standing in its centre. This is a later addition designed by Sir Swinton Jacob in a clash of styles that covers Islam, Rajput and European that now houses a museum of royal costumes and souvenirs. The most fantastic exhibit is the clothing worn by Maharaja Singh I. It is 2 metres in length, 3.5 metres round the chest and a staggering 7 metres round the waist.

By all accounts, the fellow was 2 metres tall, 1.2 metres wide and weighed a dainty 250Kg. The width of his underpants would easily consume four normal people. I suppose he needed plenty of energy to keep his 108 wives content.

In the next courtyard is the Diwan-i-Khas (hall of the private audience), made from pink and white marble and wonderfully carved, in which stand two gigantic silver urns. These were made for Maharaja Madha Singh, a devout Hindu, so that he could take sufficient holy water from the River Ganga for bathing purposes when he went to England to attend the coronation of King Edward VII. Each vessel contains 4,000 litres of the smelly river water and they have been recognised by the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest sterling silver objects in the world.

The palace’s inner courtyard (Pitnam Niwas Chowk) has four glorious gates representing the four seasons. Undoubtedly, the most magnificent is the Peacock Gate, depicting autumn, with intricate, swirling patterns and peacock motifs. Around the doorway are five beautiful and identical peacock bas reliefs in all their feathered glory. The four gates together make this a wonderful courtyard that must have witnessed many splendid parties.

The current Maharaja’s residential palace stands slightly apart from all this. A five storey high square block painted, curiously, in yellow. From the top flew the flag of the Jaipur royal family that is twinned with a smaller, quarter flag that flew above it. Apparently Maharaja Jai Sing was a cheeky chap and sufficiently impressed Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb with his forwardness when they met that the Emperor conferred on Jai Singh the title ‘Sawai’, meaning one and a quarter. It’s a title carried by his descendants ever since and repeated in the flag. We wanted to have a look inside the current palace but Debbie had left our invitation to take tea with His Highness in the hotel so we were thrown out.

The most unusual place in Jaipur is the Jantar Mantar. The name is derived from Sanskrit and means ‘instrument of calculation’. It was a place built by Jai Singh in 1728 as an observatory and is full of great sculptures that were used to measure the position and track of the stars, their altitude and azimuth and for calculating eclipses. Essentially, most of the instruments did the same job and their enormous size allowed for very accurate measurement.

The most unusual place in Jaipur is the Jantar Mantar. The name is derived from Sanskrit and means ‘instrument of calculation’. It was a place built by Jai Singh in 1728 as an observatory and is full of great sculptures that were used to measure the position and track of the stars, their altitude and azimuth and for calculating eclipses. Essentially, most of the instruments did the same job and their enormous size allowed for very accurate measurement.

The king of the instruments is a sundial. It’s not the sort of thing that can fit into a back garden with a 27 metre gnomonic arm set at an angle of 27 degrees (the same as the latitude of Jaipur). The shadow that is cast moves at up to 4 metres an hour and aids in the calculation of local and meridian time, to n accuracy of 2 seconds! It can also be used to calculate various attributes of the heavenly bodies including declination (the angular distance of a heavenly body from the celestial equator) and altitude. Most of the explanations as to how the instruments worked was, frankly, mumbo jumbo, unless you have a degree in Astrology and/or are interested in that sort of thing. Nonetheless, it was fun trying to work out how the contraptions may have been used and what day to day purpose they may have served.

The king of the instruments is a sundial. It’s not the sort of thing that can fit into a back garden with a 27 metre gnomonic arm set at an angle of 27 degrees (the same as the latitude of Jaipur). The shadow that is cast moves at up to 4 metres an hour and aids in the calculation of local and meridian time, to n accuracy of 2 seconds! It can also be used to calculate various attributes of the heavenly bodies including declination (the angular distance of a heavenly body from the celestial equator) and altitude. Most of the explanations as to how the instruments worked was, frankly, mumbo jumbo, unless you have a degree in Astrology and/or are interested in that sort of thing. Nonetheless, it was fun trying to work out how the contraptions may have been used and what day to day purpose they may have served.

It was very clear what purpose Nahargarh served. It is a fort that stands at the top of a sheer ridge looking over Jaipur. It looks really impressive from the city but doesn’t seem much when we get there having negotiated an 8Km switchback road up the hillside. This may be because, after the British arrived and undertook to protect the region, Maharaja Ram Singh adapted it to house nine of his numerous wives. The Madhavendra Bhawan was constructed with nine spacious apartments, all with great views and full of the mod cons of the day and all nicely decorated. The rooms are linked by a maze of twisting corridors so that the king could visit any of his queens without the others’ knowledge.

Nearby is the much more defensively sound fort of Jaigarh that stands at the top of a scrubby green hill known as Cheel ka Teela (Mound of Eagles). We didn’t see any eagles but, we have to report, that this is a proper defensive institution. It does not have the whimsical, palatial frills found in most other large Rajput forts, probably because the rulers lived in palaces below. It has its own reservoirs fed by sophisticated rainwater harvesting systems that feed three large tanks, one of which can hold 23 million litres of water.

Nearby is the much more defensively sound fort of Jaigarh that stands at the top of a scrubby green hill known as Cheel ka Teela (Mound of Eagles). We didn’t see any eagles but, we have to report, that this is a proper defensive institution. It does not have the whimsical, palatial frills found in most other large Rajput forts, probably because the rulers lived in palaces below. It has its own reservoirs fed by sophisticated rainwater harvesting systems that feed three large tanks, one of which can hold 23 million litres of water.

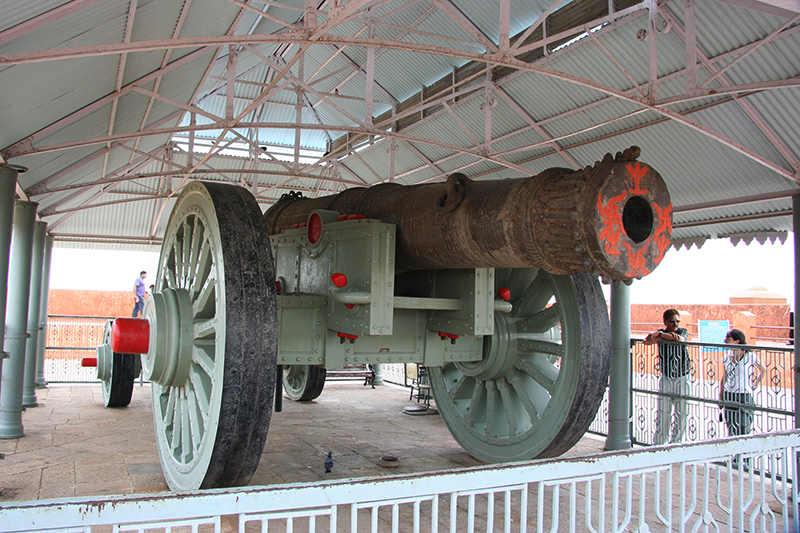

It also has the world’s largest wheeled cannon, Jaya Vana. The cannon dates from 1720 and has a barrel 6 metres long made from a mixture of eight different metals that manage to give it an all up weight of 50 tonnes. To fire it requires 100Kg of gunpowder and, it is said, to have a range of 40Km. It was only fired once, as a test, and the explosion within the barrel nearly shook the fort to pieces. I would have thought that firing a cannon ball over a range of 40Km would be so inaccurate as to be useless.

It also has the world’s largest wheeled cannon, Jaya Vana. The cannon dates from 1720 and has a barrel 6 metres long made from a mixture of eight different metals that manage to give it an all up weight of 50 tonnes. To fire it requires 100Kg of gunpowder and, it is said, to have a range of 40Km. It was only fired once, as a test, and the explosion within the barrel nearly shook the fort to pieces. I would have thought that firing a cannon ball over a range of 40Km would be so inaccurate as to be useless.

While walking the walls, we came across a Bollywood movie in the making. An area of the fort had been decorated with bright cloth and a host of dancers and extras in red, green and yellow costumes twirled and swirled to the beat of techno-Indi music. We watched proceedings for quite a while expecting to be asked to take centre stage for the action shots, or to take over as body doubles for the stars, but the production staff steadfastly ignored us. So we wandered away to admire the distant views from the top of the ramparts.

While walking the walls, we came across a Bollywood movie in the making. An area of the fort had been decorated with bright cloth and a host of dancers and extras in red, green and yellow costumes twirled and swirled to the beat of techno-Indi music. We watched proceedings for quite a while expecting to be asked to take centre stage for the action shots, or to take over as body doubles for the stars, but the production staff steadfastly ignored us. So we wandered away to admire the distant views from the top of the ramparts.

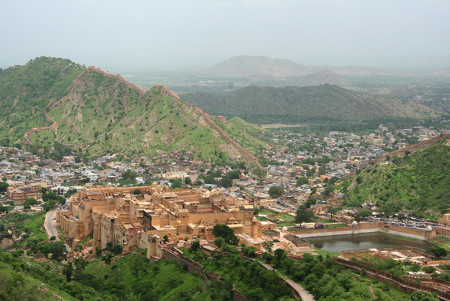

The one spectacular view that Jaigarh has is over the wonderful Amber Fort below. This is really more of a palace than a fort and it relied on Jaigarh to stand sentry and guard over it. Amber Fort is a striking edifice standing half way up a hill and accessible only from a winding road that snakes along the bottom of the battlements. It is built from pale red sandstone and white marble and is complete with coloured inlays and magnificent entranceways.

The main courtyard, Jaleb Chowk, is big enough to house an army all by itself and it is where returning conquerors would display war booty gained from a successful military campaign. From here, a grand staircase leads up to the second courtyard which holds the Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience) in which the Maharaja would hear the petitions, complaints and quarrels of his people.

To one side of the courtyard, at the top of another climb of steps, is the fabulous Ganesh Pol Gate. This is richly decorated with carvings and inlays and is the beginning of the private quarters. No expense was spared for any area that the Maharajah used – the fabulously opulent Jai Mandir, for example, with inlaid panels and reflective mirrors – but everyone else was expected to live more frugally. Regrettably, no one is allowed inside the most wonderful rooms and we are left to imagine the interior of the Sukh Niwas (Hall of Pleasure) from outside locked doors.

Like the apartments in Nahargarh Fort, the women’s Zenana section is designed so that the maharaja could conduct his nocturnal visits to his wives and concubines unobserved. He must have had a particularly quarrelsome and politicking bunch of women to have gone to such length to keep his activities secret.

I have to say that the food in Jaipur has not been up to the standard of the rest of Rajasthan. It is much more like the typical Indian restaurant back in the UK. Soft and mushy. Not only that but they managed to give me ‘Delhi Belly’ and an entire night enjoying the delights of sitting on a toilet. Pills eventually blocked me up but now I have the opposite problem.

I can’t say that we have warmed to the music I’m sorry to report. To me the vocal wailing sounds like some poor chap is being given a vasectomy without anaesthetic, while, in the background, rabid sitar players twang away an entirely different tune. Still, we can’t be expected to like everything.

Jaipur is certainly a city that has diverse attractions and a remarkable heritage given its short history. It is fittingly the capital of Rajasthan and an axis of India’s Golden Triangle that includes Delhi and Agra. On the one hand it has fairy tale grandeur and, on the other, it is just as dirty and full of annoyances as every other Indian city.

No comments yet.