It’s Ramadan, it’s boiling hot and we’ve made it as far as Fes in Morocco. The easiest way to get here from Zanzibar would have been to fly into Europe and then back out again, but that seemed gutless. The hardest way would have been to walk but that, I’m ashamed to say, held even less appeal. So we went on a complicated circle, flying to Cairo via Khartoum, hanging about for six hours before flying to Casablanca and finally jumping on a train. It only took 28 hours.

During the Muslim fast of Ramadan believers are not allowed to eat or drink (not even water) from sunrise to sunset and it lasts for a lunar month. When it occurs during the summer months it’s very hard on the faithful, not just because summer daylight lasts much longer than in winter but the heat (over 40c every day) makes for grumpy and lethargic locals. They meander about in the zombie-like state of the undead or find a bit of shade and sleep. There were times when we thought our guide, Hicham, was going to pass out. The only relief they get is to splash their face with water either from the fountains outside a mosque or from a water bottle fixed with a makeshift nozzle.

At 7.00pm when a calling Imam announces the end of the day’s fast there is almost a audible sigh of relief as great quantities of non alcoholic drink get consumed as everyone returns to normality. It’s also a time of family gathering as members come together to eat. We were fortunate enough to be invited by Hicham to break the fast with his family evening meal at his mother’s house. We were treated to an enormous spread prepared by his mother and cousin comprising soup, vegetarian tagine, bread, cheese, dried meat, grapes, banana, dates, figs, juice and water. The surprising thing was how little our hosts ate. They said that after 15 days of fasting already, they no longer had much of an appetite.

At 7.00pm when a calling Imam announces the end of the day’s fast there is almost a audible sigh of relief as great quantities of non alcoholic drink get consumed as everyone returns to normality. It’s also a time of family gathering as members come together to eat. We were fortunate enough to be invited by Hicham to break the fast with his family evening meal at his mother’s house. We were treated to an enormous spread prepared by his mother and cousin comprising soup, vegetarian tagine, bread, cheese, dried meat, grapes, banana, dates, figs, juice and water. The surprising thing was how little our hosts ate. They said that after 15 days of fasting already, they no longer had much of an appetite.

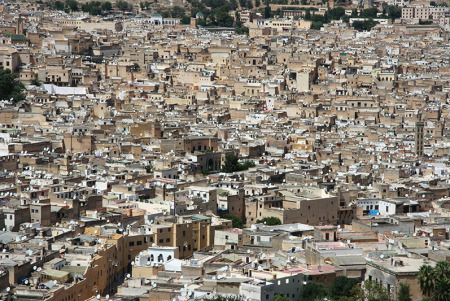

Fes (or Fez as it is sometimes known – a variation brought about because fes in French means arse), is a fascinating city; as near to the Middle Ages as you can get in a couple of hours by air from Europe. It is not an easy city to get to know as it is made up of an interminable number (40,000 apparently) of twisting narrow alleyways, many of which (9,000) are dead ends. But the persistent explorer will unearth the city’s treasures of historic buildings centred around the famous Qaraouiyine Mosque and some interesting souks.

Fes (or Fez as it is sometimes known – a variation brought about because fes in French means arse), is a fascinating city; as near to the Middle Ages as you can get in a couple of hours by air from Europe. It is not an easy city to get to know as it is made up of an interminable number (40,000 apparently) of twisting narrow alleyways, many of which (9,000) are dead ends. But the persistent explorer will unearth the city’s treasures of historic buildings centred around the famous Qaraouiyine Mosque and some interesting souks.

Fes has a highly strategic location situated in the Oued (river) Sebou basin, astride the traditional trade route from the Sahara to the Mediterranean as well as on the path from Algeria, and the Islamic heartland beyond, into Morocco. For years the dominant axis within Morocco was between Fes and Marrakech, two cities linked by their power as well as their rivalry. Even today, while the coastal belt centred on Rabat and Casablanca dominates the country in demographic, political and economic terms, Fes continues to be the religious and spiritual capital of Morocco.

Founded in AD808 by Idriss II, El Azhar (the splendid), the city gravitated around the Cathedral-mosque where Moulay Idriss and his descendants are buried. The people of Fes are deeply religious. Dr Edmond Secret, writing in his diary during the 1930s said that “the majority do their five daily prayers. Draped in modesty in the enveloping folds of their cloaks, the bourgeois, prayer carpets under their arms, recall monks in their dignity. The air of religiosity clings to the city, especially during Ramadan.”

Founded in AD808 by Idriss II, El Azhar (the splendid), the city gravitated around the Cathedral-mosque where Moulay Idriss and his descendants are buried. The people of Fes are deeply religious. Dr Edmond Secret, writing in his diary during the 1930s said that “the majority do their five daily prayers. Draped in modesty in the enveloping folds of their cloaks, the bourgeois, prayer carpets under their arms, recall monks in their dignity. The air of religiosity clings to the city, especially during Ramadan.”

The city’s religious life was closely tied to education. “If learning was born in Medina, maintained in Mecca and milled in Egypt, then it was sieved in Fes”, goes and old adage. Fes supplied the intellectual elite of the country along with many of its merchants, and Fassis (the people of Fes) are to be found in most towns and cities. They are rightly proud of their city: their self confidence, verging on self satisfaction at times, is a distinctive trait. But despite all this wonderful heritage, the draw of Rabat as the country’s capital and seat of power, has slowly sucked all the rich and intellectuals from the city.

Walking around, it is noticeable how much of the medina is dilapidated and desperately in need of urgent renovation. As the rich elite moved to the Atlantic coast, they left their grand houses in the care of their poorer relatives or to rural immigrants. The money for the upkeep of large, ageing buildings has gone elsewhere, leaving the medina facing critical problems, not the least of it is the pollution of the Oueds (rivers) Fes and Sebou along with the disintegration of the historic, but much decayed, drinking water system. The drinking water, believes Hicham, killed his father who died of hepatitis.

In addition, 35% of the population lives beneath the poverty line and the agency set up to improve living conditions has had little success. Houses, which are mostly built from sand mixed with stone and occasional bands of wood, are disintegrating during the winter rains. Wherever we go, buildings are being propped up by large scaffolds of wood and gaps mark the spot where entire structures have collapsed. The World Bank thinks that US$14 million is required for infrastructure improvements but, I think, they’ve left a zero off their figures.

Nonetheless, the grand buildings within the medina and the main gates are magnificent. The main gate from our Riad was the Bab Boujloud, coloured blue on the outside (the colour of Fes) and green on the inside (the colour of Islam). Just inside the gate, a large number of small restaurants vie for business before we get swallowed up in the narrow alleys that are lined with small local shops selling sweet, honeyed breads, meat, vegetables, spices, clothing and tourist tat. Within minutes we feel as if we have entered another world. The cobbled alleys, just about wide enough for two people to pass, are squashed between tall crumbling buildings that shut out the heat of the sun. None of the walkways have names and we feel that the maize of twisting streets is designed to lose the innocent, fresh visitor and hold them in its prison.

Nonetheless, the grand buildings within the medina and the main gates are magnificent. The main gate from our Riad was the Bab Boujloud, coloured blue on the outside (the colour of Fes) and green on the inside (the colour of Islam). Just inside the gate, a large number of small restaurants vie for business before we get swallowed up in the narrow alleys that are lined with small local shops selling sweet, honeyed breads, meat, vegetables, spices, clothing and tourist tat. Within minutes we feel as if we have entered another world. The cobbled alleys, just about wide enough for two people to pass, are squashed between tall crumbling buildings that shut out the heat of the sun. None of the walkways have names and we feel that the maize of twisting streets is designed to lose the innocent, fresh visitor and hold them in its prison.

The locals scurry about as best they can during Ramadan, trying to keep away from the heat of the day. Many doze in doorways or behind their shops. Donkeys and mules looking horrendously overladen are the only means of transporting goods around the city, often carrying their owners as well, and shuffle around as they are continuously arranged with tongue and stick. When one of these beasts comes down an alleyway everyone scampers out of the way for they don’t stop for anyone and take up all the available space. Some are shod with rubber shoes making it difficult to hear them coming up behind; a forceful nudge in the back and a shout from the driver often being the first we know of their approach.

The locals scurry about as best they can during Ramadan, trying to keep away from the heat of the day. Many doze in doorways or behind their shops. Donkeys and mules looking horrendously overladen are the only means of transporting goods around the city, often carrying their owners as well, and shuffle around as they are continuously arranged with tongue and stick. When one of these beasts comes down an alleyway everyone scampers out of the way for they don’t stop for anyone and take up all the available space. Some are shod with rubber shoes making it difficult to hear them coming up behind; a forceful nudge in the back and a shout from the driver often being the first we know of their approach.

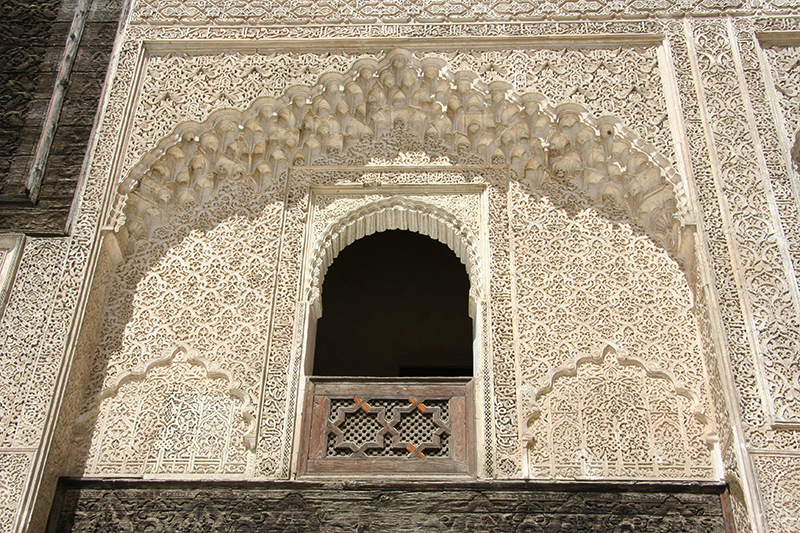

The jewel of Fes is undoubtedly the medersa (school) Bou Anania and rightly considered one of the finest in existence. When the Sultan was presented with the accounts of the building of this magnificent construction, he tore up the paperwork declaring “Beauty is not expensive, whatever the sum may be. A thing which pleases man cannot be paid too dear.” A sentiment echoed by every wife when her husband is buying her birthday present.

Stepping inside the grand doors the interior courtyard is breathtaking. The walls are intricately carved in the Islamic style, verses from the Koran are written in extravagant calligraphy all around, the wooden lattice work of the upper floor is carved in complicated, interweaving patterns and the marble floor has a fountain in its centre. High vaulted ceilings are made of cedar wood, which when warmed by the sun fills rooms with a beautiful perfume. The doors that lead off the courtyard are grand and imposing. The whole construction is quite magnificent.

Stepping inside the grand doors the interior courtyard is breathtaking. The walls are intricately carved in the Islamic style, verses from the Koran are written in extravagant calligraphy all around, the wooden lattice work of the upper floor is carved in complicated, interweaving patterns and the marble floor has a fountain in its centre. High vaulted ceilings are made of cedar wood, which when warmed by the sun fills rooms with a beautiful perfume. The doors that lead off the courtyard are grand and imposing. The whole construction is quite magnificent.

To get from school to the university, which is open to all, a student has to pass a number of tests. Some of these involve having to memorise the entire Koran and being able to recite 1,000 verses of poetry. Although the university is theology based, it covers all disciplines as long as the student recognises that god is the hand behind all creation.

To get from school to the university, which is open to all, a student has to pass a number of tests. Some of these involve having to memorise the entire Koran and being able to recite 1,000 verses of poetry. Although the university is theology based, it covers all disciplines as long as the student recognises that god is the hand behind all creation.

The other big site is nearby. The Mosque Qaraouiyine was built in AD859 (245 in Muslim years) by a lady called Fatima Al-Fihria. It is built on a massive site of 14 acres and can contain 14,000 worshippers at any time. From the little streets, it doesn’t look this large but we can only peer inside from the doorway.

There are many mosques dotted about the city, underlining the strong religious influence. The Mosque Jamaa Andalous in the Spanish quarter is famous for having the biggest gate in the city. Other, less grandiose mosques, are full to overflowing for evening prayers with people standing in the streets in rows four or five deep.

Fes also has an enormous royal palace that stands on 83 hectares (over 200 acres) and accounts for 25% of the total area of the city. It is the biggest in Morocco but not often visited by the king unless he is on holiday. The entrance has 7 bronze doors that reflect the days of the week that have been made by hand by the city’s artisans as a gift to their monarch. Interestingly, although Morocco is supposed to be a democracy and holds elections every 6 years, it is the king who appoints ministers regardless of whether they have been elected. He still holds most of the power in the country and is held in great esteem.

Overlooking the palace on a nearby hill stands the great vantage point of Fes. The fortress of Borj Nord built by Ahmad al Mansour in 1582 but looking fresh and restored. From here, we have fine views in all directions and it is very apparent how the city is held in the palm of the middle Atlas Mountains. The flat rooftops of the city are almost completely obliterated by satellite dishes. Every house has at least one. Even a ramshackle, beaten up, lean-to has a dish. The city’s buildings are so squashed together that even our guide cannot point out any of the important sites. The only identifiable area is the tanneries.

We know when we are near the Chouara tanneries because the smell permeates the air all around. It’s the pungent mix of camel urine and guano that is used to turn animal hides into dyed, useable leather. The tannery has not changed since medieval times and sucks water from the Oued Boukhareb, returning its cloying waste into the same river. The initial process involves the urine and guano so that remaining hair can be easily scrapped off after an immersion of a week. The hide is then immersed again for another week so that the remaining fat can be removed before it is left in a vat of dye for two weeks prior to being dried in the sun. It is then ready to be put to effective use. Judging by the product showrooms, Fes is not renowned for its leather goods and there seems little prospect of that changing.

We know when we are near the Chouara tanneries because the smell permeates the air all around. It’s the pungent mix of camel urine and guano that is used to turn animal hides into dyed, useable leather. The tannery has not changed since medieval times and sucks water from the Oued Boukhareb, returning its cloying waste into the same river. The initial process involves the urine and guano so that remaining hair can be easily scrapped off after an immersion of a week. The hide is then immersed again for another week so that the remaining fat can be removed before it is left in a vat of dye for two weeks prior to being dried in the sun. It is then ready to be put to effective use. Judging by the product showrooms, Fes is not renowned for its leather goods and there seems little prospect of that changing.

The one bright note for Fes is that it has a fast increasing number of upmarket riads (guest houses) springing up all around the city and an increasing number of European owned hotels, cafes and restaurants. This outside investment and the economic benefits that flood from new visitors should help the old city revive. We hope that it does because it is a fascinating place to spend a few days. The people were very kind to us and were keen that we should encourage others to visit the city. The traditional products (carpets, pottery and metal goods such as lanterns and jewellery) were of an excellent standard though we have to stand our ground very firmly in the face of hard selling.

The one bright note for Fes is that it has a fast increasing number of upmarket riads (guest houses) springing up all around the city and an increasing number of European owned hotels, cafes and restaurants. This outside investment and the economic benefits that flood from new visitors should help the old city revive. We hope that it does because it is a fascinating place to spend a few days. The people were very kind to us and were keen that we should encourage others to visit the city. The traditional products (carpets, pottery and metal goods such as lanterns and jewellery) were of an excellent standard though we have to stand our ground very firmly in the face of hard selling.

No comments yet.