We land in Beijing (Chinese for North Capital) after a short stop over in Hong Kong. It’s cold. Six centigrade, overcast with that cold, wet fog that works its way into the bones. Fortunately, we had anticipated cooler weather and did not need to revert to breaking open the backpacks for sweaters but this weather is too much like being at home. The locals were complaining of the coldest winter for many years with the temperature in the city dropping as low as -17c. I was not sure whether this was to reassure us or to apologise but, apparently, it is usually about 20c at this time of year.

Driving from the airport, we were struck at once by the amount of concrete everywhere. Boy there must be millions and millions of tons of it in buildings, roads, flyovers and runways that evolve into concrete apartment blocks, housing and gargantuan government buildings. In the drizzle everything took on a drabness that sank the soul.

‘So great a number of houses and people, no man could tell the number…’ So said Marco Polo in the 13th century and it still seems true today. Beijing covers an area of 17,000 sq km, roughly the size of Belgium, and is home to 16 million people (mas o menos as the Spanish would say). That’s about 1 in 100 Chinese people and growing all the time. China has a huge net city migration of 10 million people a year as countrysiders move to the cities leaving the children at home in the care of grandparents.

‘So great a number of houses and people, no man could tell the number…’ So said Marco Polo in the 13th century and it still seems true today. Beijing covers an area of 17,000 sq km, roughly the size of Belgium, and is home to 16 million people (mas o menos as the Spanish would say). That’s about 1 in 100 Chinese people and growing all the time. China has a huge net city migration of 10 million people a year as countrysiders move to the cities leaving the children at home in the care of grandparents.

They are coming to the cities, and Beijing in particular, looking for better opportunities as China changes at an astonishing pace. There is a social revolution every bit as radical as Mao Zedong’s 1960s Cultural Revolution. We can still see some of the old Beijing: a bicycle repairer squatting on a street corner with his tools, waiting for a passing cyclist with a puncture; down an adjoining hutong (small alley or lane) people still insulate their homes with newspaper.

They are coming to the cities, and Beijing in particular, looking for better opportunities as China changes at an astonishing pace. There is a social revolution every bit as radical as Mao Zedong’s 1960s Cultural Revolution. We can still see some of the old Beijing: a bicycle repairer squatting on a street corner with his tools, waiting for a passing cyclist with a puncture; down an adjoining hutong (small alley or lane) people still insulate their homes with newspaper.

But evidence of a new society is everywhere as Beijingers embrace consumerism with revolutionary fervour. Everyone has a mobile phone, youngsters (especially the girls) dress in western style clothing, foreign cars (Mercedes, BMW, Volkswagen, even Ferraris as well as all the Japanese carmakers) are commonplace, digital cameras are pointing in all directions and western style office complexes, shopping centres and designer labels dominate the centre of town. According to the Asian Financial Times I was reading, China’s GDP grew at a rate of over 10% in the last quarter and the citizens are busy spending. It seems that the Chinese are intent on taking over the world economically.

But evidence of a new society is everywhere as Beijingers embrace consumerism with revolutionary fervour. Everyone has a mobile phone, youngsters (especially the girls) dress in western style clothing, foreign cars (Mercedes, BMW, Volkswagen, even Ferraris as well as all the Japanese carmakers) are commonplace, digital cameras are pointing in all directions and western style office complexes, shopping centres and designer labels dominate the centre of town. According to the Asian Financial Times I was reading, China’s GDP grew at a rate of over 10% in the last quarter and the citizens are busy spending. It seems that the Chinese are intent on taking over the world economically.

But it has been like this only recently. Beijing became important following the Mongol invasion in 1215 when Genghis Khan annexed much of the country and his grandson Kubla Khan established his capital here of the largest empire the world has ever known. When the Ming Dynasty defeated the Mongols in 1368, the capital was to the south in Nanjing (Chinese for southern capital) but soon returned and Emperor Yongle became the architect of great buildings such as the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven, erecting them on the ruins of the palace on the crushed Mongols. Over the centuries successive invaders occupied Beijing, sometimes destroying and sometimes altering the magnificent buildings, but the shape and the symmetry of the city was maintained.

Modern Beijing came of age when, in January 1949, the People’s Liberation Army entered the city and Mao Zedong proclaimed a ‘Peoples Republic’ from Tiananmen Gate to an audience of 500,00 citizens.

Like the Emperors before them, the communists significantly altered the face of the city to suit their own image. Imperial archways were brought down, whole city blocks were bulldozed to widen boulevards, and the outer walls were leveled in the interests of traffic circulation. Soviet experts and technicians poured in, bringing their own Stalinesque touches.

But recent economic progress has transformed Beijing into a modern city with shopping malls, skyscrapers and heaving flyovers. The metro is stainless steel clean, efficient, up to date and cheap. Green spaces and street trees try to change the concrete jungle into a greener, cleaner and more pleasant place for the millions of city dwellers and the thousands upon thousands of visitors.

It certainly feels like the whole of China is here when we are crammed into the metro or walking around the big tourist sites that are filled with people. Apparently, about 90% of our fellow visitors in this city are Chinese, all following tour leaders who hold coloured flags for their flock to follow and bark instructions through electronic megaphones. In the tight spaces, over narrow bridges or through the great gates we waddle along like ducks, standing shoulder to shoulder and stomachs to bottoms (or knees mostly). I thank my parents a million times for my height.

Even the vast desert of paving stones that is Tiananmen Square, which we are told can hold one million people, there does not seem to be much space. Much of it is taken up by the huge mausoleum to ‘the great helmsman’ himself, Chairman Mao, and the queue to look at his mummified body snakes all around the building and into the remainder of the square. I suppose this is a fitting resting place for Mao who conceived the square to project the enormity of the communist party and vast, open, concrete desert is an apt description of them both.

Even the vast desert of paving stones that is Tiananmen Square, which we are told can hold one million people, there does not seem to be much space. Much of it is taken up by the huge mausoleum to ‘the great helmsman’ himself, Chairman Mao, and the queue to look at his mummified body snakes all around the building and into the remainder of the square. I suppose this is a fitting resting place for Mao who conceived the square to project the enormity of the communist party and vast, open, concrete desert is an apt description of them both.

There is no sign or mention of the pro democracy demonstrators of 1989; they have become barely a footnote of Beijing history as modernity has been embraced without political evolution. There is a conspicuous absence of protest in the city and we saw no subversive graffiti or wall posters.

At the northern end of Tiananmen Square lies the Gate of Heavenly Peace where the great helmsman and his acolytes reviewed mass troop parades and where an enormous portrait of Mao hangs above the main entrance like a god watching over his people. The magnificent gate marks the beginning of the Forbidden City, so called because it was off limits for 500 years to all but the Emperor, his family and staff (around 7,000 people). The price for uninvited admission was instant execution.

It was home to two dynasties of emperors, the Ming and the Qing, and it is the largest and best preserved cluster of ancient buildings in China. Dating from 1420, the Forbidden City covers an area nearly one square kilometer on a north-south axis. As we enter, there are a series of reception buildings down the central axis whose floor level steadily rise higher until we reach the Emperor’s reception and business hall, the biggest wooden structure in China. There are numerous buildings off to the sides of this inner city that housed all the people and supplies that were necessary to run the Emperor’s complicated life and needs. There are areas for the Emperor himself (which did not seem to be particularly large or lavish), his Empress, his concubines (of which there could be up to 100), the royal family (which includes all relatives), assorted hangers on, soldiers and servants. Unfortunately, as seems to be the case everywhere, we could not get inside any of the buildings, so we were reduced to fighting for space to peer into the unlit interior either at a door or window. Evidently, the communist principles of common ownership do not apply to visiting national monuments.

It was home to two dynasties of emperors, the Ming and the Qing, and it is the largest and best preserved cluster of ancient buildings in China. Dating from 1420, the Forbidden City covers an area nearly one square kilometer on a north-south axis. As we enter, there are a series of reception buildings down the central axis whose floor level steadily rise higher until we reach the Emperor’s reception and business hall, the biggest wooden structure in China. There are numerous buildings off to the sides of this inner city that housed all the people and supplies that were necessary to run the Emperor’s complicated life and needs. There are areas for the Emperor himself (which did not seem to be particularly large or lavish), his Empress, his concubines (of which there could be up to 100), the royal family (which includes all relatives), assorted hangers on, soldiers and servants. Unfortunately, as seems to be the case everywhere, we could not get inside any of the buildings, so we were reduced to fighting for space to peer into the unlit interior either at a door or window. Evidently, the communist principles of common ownership do not apply to visiting national monuments.

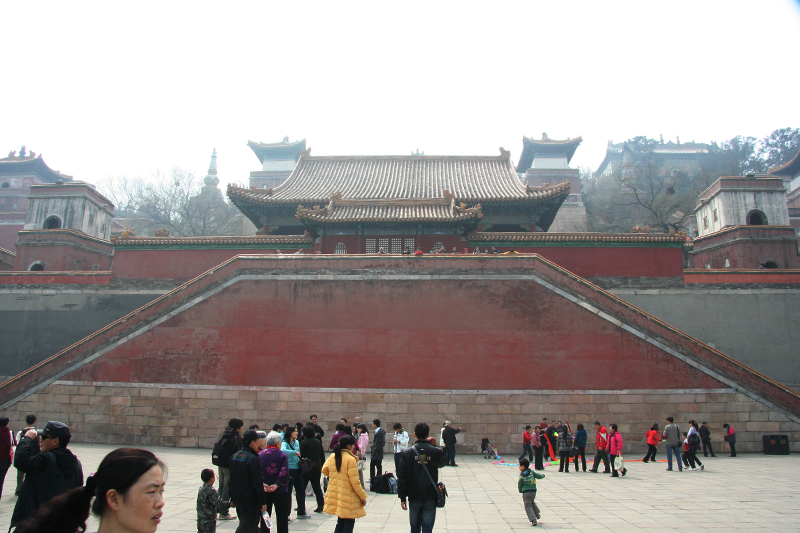

Unfortunately, the same restrictions applied to the great Summer Palace. Originally built as a garden, it was turned into summer living quarters by the Emperor Qianlong in 1750 as a 60th birthday present for his mother. The royal court took refuge here from the roasting summer heat of the Forbidden City in this opulent dominion of palace temples, gardens pavilions, corridors and large, glittering lake.

The lake, shaped like a peach – the Chinese sign of longevity, dominates the garden, swallowing up nearly three quarters of the site. It was dug out and extended by 100,000 workers and the excavated dirt was used to shape and heighten the surrounding landscape. The pavilions, temples and associated buildings are all magnificent, traditional Chinese design with complicated and highly decorative roofs and facades but with simple large space interiors. Several of the buildings simply house Buddha statues with the largest building, the Buddha Incense Tower dominating an elevated position above the lake, housing a statue of the Guanyin Bodhisattva, a female Buddha that supposedly has 1,000 eyes and 1,000 hands. As we all know, it signifies the female ability to see and know everything and to help everyone. To complete the reverence, the statue sits on 9 layers of 99 petals.

The lake, shaped like a peach – the Chinese sign of longevity, dominates the garden, swallowing up nearly three quarters of the site. It was dug out and extended by 100,000 workers and the excavated dirt was used to shape and heighten the surrounding landscape. The pavilions, temples and associated buildings are all magnificent, traditional Chinese design with complicated and highly decorative roofs and facades but with simple large space interiors. Several of the buildings simply house Buddha statues with the largest building, the Buddha Incense Tower dominating an elevated position above the lake, housing a statue of the Guanyin Bodhisattva, a female Buddha that supposedly has 1,000 eyes and 1,000 hands. As we all know, it signifies the female ability to see and know everything and to help everyone. To complete the reverence, the statue sits on 9 layers of 99 petals.

It is not possible to gain a real feeling of the magnificence of this or other artifacts because they are all covered in years of dust. The official reason for this is that cleaning them will cause damage by removing the thin layer of gold gilt that adorns their exterior, but, I suspect, the dust protects them from the acidic atmosphere of Beijing pollution.

As can be seen from our photographs, the polluted atmosphere shuts down the views of the city from the elevated positions in the Summer Palace and, even the far side of the lake, disappears in a mist (despite the sun’s best efforts to lighten the day). Through the murk, it is possible to see the island in the middle of the lake that is connected to the shore by a wonderful 17 arch bridge. It is 150 metres long and has 500 stone carved lions lining the route across the lake. Four odd but complicated carvings guard the start and finish and the whole wonderful construction represents an outstanding example of Qing dynasty stone carving skills. That and the long corridor of hand painting, depicting different areas of China, were the only work of art that we could touch and admire close up.

As can be seen from our photographs, the polluted atmosphere shuts down the views of the city from the elevated positions in the Summer Palace and, even the far side of the lake, disappears in a mist (despite the sun’s best efforts to lighten the day). Through the murk, it is possible to see the island in the middle of the lake that is connected to the shore by a wonderful 17 arch bridge. It is 150 metres long and has 500 stone carved lions lining the route across the lake. Four odd but complicated carvings guard the start and finish and the whole wonderful construction represents an outstanding example of Qing dynasty stone carving skills. That and the long corridor of hand painting, depicting different areas of China, were the only work of art that we could touch and admire close up.

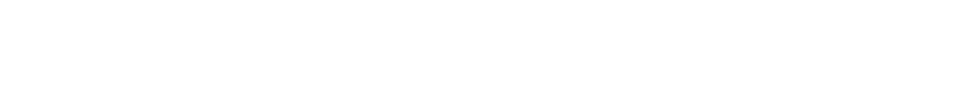

Getting close to a good map was also a challenge. We did not try overly hard but the only maps we had were from our guide book or ‘withdrawn’ from a city guide. On our first day in a city we like to walk wherever we can so as to get a feel for the place, but we made the mistake of not looking at the scale of our little map before setting off and naturally felt that sights an inch or so apart could be easily walked from one to another. The distances turned out to be enormous and, apart from a brief break for lunch and dinner, we returned to our B&B after 10 hours walking. We just sneaked into the magnificent Lama Temple before throwing out time but the upside was that it was free of the pressing crowds we had encountered elsewhere.

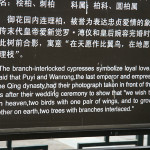

It is the most renowned Buddhist temple outside Tibet having been converted into a lamasery in 1744 after serving as the residence of Emperor Yong Zhen. Flaunting beautiful rooftops, stunning frescoes, magnificent decorative arches, tapestries, intricate carpentry, impressive statues and fierce lions, it is enthralling. Pilgrims burn whole bunches of incense outside the buildings that hold the Buddha statues, waving it about their heads as they bow in reverence, before throwing the left-overs into a large bbq-like brassier and confronting their gods. We could get into the buildings here, at least, but no photographs were allowed.

It is the most renowned Buddhist temple outside Tibet having been converted into a lamasery in 1744 after serving as the residence of Emperor Yong Zhen. Flaunting beautiful rooftops, stunning frescoes, magnificent decorative arches, tapestries, intricate carpentry, impressive statues and fierce lions, it is enthralling. Pilgrims burn whole bunches of incense outside the buildings that hold the Buddha statues, waving it about their heads as they bow in reverence, before throwing the left-overs into a large bbq-like brassier and confronting their gods. We could get into the buildings here, at least, but no photographs were allowed.

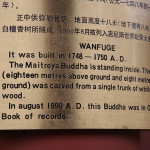

The final temple hall, called the Wanfu Pavilion, contains a magnificent statue of the Maitreya Buddha in his Tibetan form, clothed in yellow satin and, reputedly, sculpted from a single block of sandalwood. It is 18 metres high and goes 8 metres into the ground. Each of the toes is the size of a pillow and there are galleries all around the effigy to enable the monks to have a closer look and, no doubt, carry out essential maintenance.

The final temple hall, called the Wanfu Pavilion, contains a magnificent statue of the Maitreya Buddha in his Tibetan form, clothed in yellow satin and, reputedly, sculpted from a single block of sandalwood. It is 18 metres high and goes 8 metres into the ground. Each of the toes is the size of a pillow and there are galleries all around the effigy to enable the monks to have a closer look and, no doubt, carry out essential maintenance.

In many ways, the most impressive aspect of this temple is that it exists at all. The communists do not believe in religion other than their own doctrine and the Tibetan Buddhists are not high on The Chairman’s dinner party guest list. However, to show that Big Brother had not forgotten them, plain clothes policeman searched every building with torches before locking the doors for the night.

Of course, no visit to Beijing would be complete without a visit to the Great Wall. It wriggles fitfully from scattered remains in Liaoning Province on the north east coast to Jiayuguan in the Gobi Desert in the south west. The original wall was begun over 2,000 years ago during the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC) and, when China was unified, separate walls that had been constructed by independent kingdoms to keep out marauding nomads were linked together. It took 10 years of hard labour, 180 million cubic metres of earth and the lives of many workers: legend has it that the bones of the dead construction workers (many of whom were political prisoners) was one of the materials used in the construction of the original core of the wall.

Of course, no visit to Beijing would be complete without a visit to the Great Wall. It wriggles fitfully from scattered remains in Liaoning Province on the north east coast to Jiayuguan in the Gobi Desert in the south west. The original wall was begun over 2,000 years ago during the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC) and, when China was unified, separate walls that had been constructed by independent kingdoms to keep out marauding nomads were linked together. It took 10 years of hard labour, 180 million cubic metres of earth and the lives of many workers: legend has it that the bones of the dead construction workers (many of whom were political prisoners) was one of the materials used in the construction of the original core of the wall.

The wall never did perform its function as an impenetrable line of defense. As Genghis Khan said, ‘The strength of a wall depends upon the courage of those that defend it.’ But it did work very well as an elevated highway, transporting people and goods across mountainous terrain. Its beacon tower system, generated by burning wolves’ dung, quickly transmitted news of enemy movements back to the capital.

Over the years, the wall fell into disrepair but great efforts are now being made to restore sections near tourist centres and everyone who steps on the wall has to pay at least one ‘entrance’ fee (we had to pay three).

Shunning the main tourist sections (partly in an effort to get away from the crowds), we opted to hike along a section of about 12km that was a two hour car drive from the city. The drive from the flat plain of Beijing to the surrounding mountains slowly unrolled the landscape as we escaped the city fug. The views slowly deepened from the 200 metres, to which we had become accustomed, revealing the distant horizon as the air cleared and the depressive claustrophobic closeness of the city centre was left behind. After about an hour in the car, the jagged peaks of the low-lying mountains spring into view. They resemble the spine of a dinosaur with sharp, well-defined, triangular points that continue in series across the skyline. Other small hills support the base of the mountainous range resembling the teeth of a dragon and completing a picture that looks as if it has come from a prehistoric story book. It is the type of scenery that, had we not been looking at it with our own eyes, we would not have believed existed.

In a belt and braces approach to avoiding the masses, we had also started early so as to get ahead of whatever crowds there might be. This turned out to be an excellent approach as we found ourselves first on the wall and could, at last, get some photos without hundreds of others in the frame.

In a belt and braces approach to avoiding the masses, we had also started early so as to get ahead of whatever crowds there might be. This turned out to be an excellent approach as we found ourselves first on the wall and could, at last, get some photos without hundreds of others in the frame.

The hike was exhilarating and the scenery stupendous as the wall wound its way along stunning mountain terrain. The wall builders did not cut any corners, constructing the wall on the very top of the highest peaks, creating a spine that snaked along the skyline. We could see forever in all directions from this amazing vantage point and there would have been no chance of an enemy sneaking up unseen by the defending soldiers.

The walk was very steep in parts, both uphill and downhill, and I became reacquainted with the full volume of my lungs. I don’t mind the uphill bits, they are just a steady grind, but they steep downhill sections make my knee caps feel as if they about to launch into space. And the sentries who originally defended the wall must have had very small feet because many of the steps were too small for my boots unless I crabbed sideways. Even Debbie’s delicate feet found it difficult to gain a proper purchase.

But it did not spoil our enjoyment of one of the most magnificent manmade structures in the world. The panoramic views, the raw beauty of the terrain, the proud ramparts standing defiant against intruders that link the sturdy towers, combined to lift our spirits and put a radiant smile on Debbie’s face. We loved it.

Debbie’s good humour extended to indulging some of the endless hawkers that hide in the towers and shout at your approach, ‘Beer, water, coca cola, tee shirt, you buy now!’ They are not easy to bat away, they follow us insisting we want to buy whatever they sell until they become concerned that walkers behind us might slip through their position without being accosted. However, we did allow ourselves to be coshed: Debbie bought a fetching Chairman Mao hat from an old man for the equivalent of £1 (after much bargaining) and she later agreed to buy some water from some pleasant ladies in return for a photograph.

After three hours of a wonderful walk, we arrived in the village of Simatai where we stopped for an extremely tasty lunch. It was the best meal we had eaten since arriving in China and very welcome after a challenging walk.

After three hours of a wonderful walk, we arrived in the village of Simatai where we stopped for an extremely tasty lunch. It was the best meal we had eaten since arriving in China and very welcome after a challenging walk.

Eating has been a subject fascinating those back home: how have we managed to get by? The short answer is not very well but, as I have rabbited on for long enough already, I shall leave the culinary tales to another time.

No comments yet.