We flew into Ayers Rock, now known as Uluru, the lands having been given back to the local people by the Australian government. The sky was clear, the air was cooked and the red desert was dotted with green scrub, trees and grass that had taken advantage of unusual rain to colour patches around waterholes. There is plenty of water several metres down in underground rivers which feed the local town but, on the surface, there is precious little. What little there is gets evaporated quickly by the dry air.

One of the world’s most recognized natural attractions, Ayers Rock itself is not alone (as we had imagined) but holds pride of place amongst numerous rocky outcrops that rise from the flat desert land. It’s fascinating because no picture conveys entirely the multidimensional grandeur of Uluru. And fascinating because the entire area is of deep cultural significance to the traditional owners, the Anangu community.

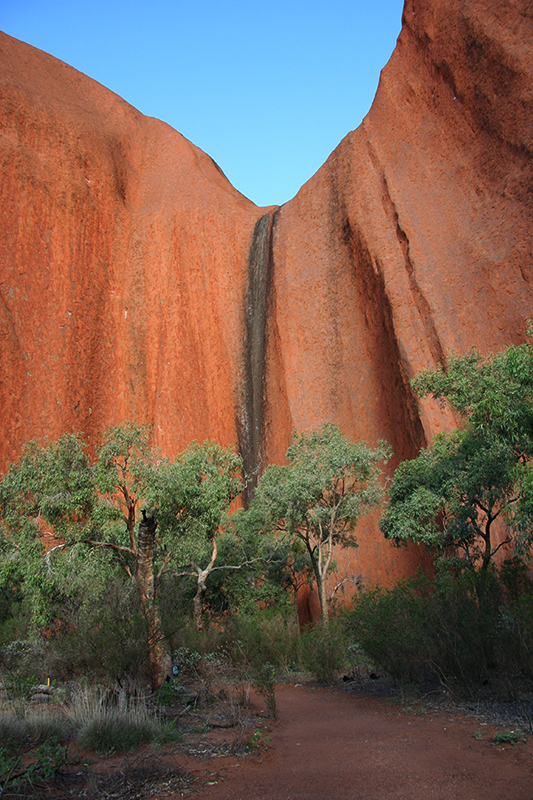

Rising 380m out of the surrounding sandy scrubland, it is 350 metres long and rose from the land 550 million years ago. It was formed by the eroded sediment from a range of mountains that, 900 million years ago, were higher than the Himalayas before weathering ground them down and almost destroyed them. Rivers washed the sediment into what is known as the Amadeus basin, where they were compressed for several hundred million years, sometimes under sea and sometimes under ice, until pressures from the Earth’s crust folded and fractured the rock. The horizontal layers of Uluru were turned 90 degrees to their current position giving the monolith vertical stripes that have been accentuated by rainwater erosion over the years. Two thirds of the rock is still underground and as the rain washes away the sandy soil around the base, it continues to rise above ground level.

Rising 380m out of the surrounding sandy scrubland, it is 350 metres long and rose from the land 550 million years ago. It was formed by the eroded sediment from a range of mountains that, 900 million years ago, were higher than the Himalayas before weathering ground them down and almost destroyed them. Rivers washed the sediment into what is known as the Amadeus basin, where they were compressed for several hundred million years, sometimes under sea and sometimes under ice, until pressures from the Earth’s crust folded and fractured the rock. The horizontal layers of Uluru were turned 90 degrees to their current position giving the monolith vertical stripes that have been accentuated by rainwater erosion over the years. Two thirds of the rock is still underground and as the rain washes away the sandy soil around the base, it continues to rise above ground level.

On the other hand, the local Anangu community has a different interpretation. According to their belief, there was nothing on earth until their ancestors – in the forms of people, plants and animals — travelled widely across the land and formed the world as we know it. The spirits of these ancestors reside in Uluru which is sacred and it is the place where the spirits of the dead travel to rest for eternity. A visit to the rock not only enables them to invoke the spirits of the creators but also to speak to the spirits of their dead. Additionally, it is the site for a number of ceremonies: initiations, marriages and funerals. The white people do not know much about the Aboriginal culture here because we are not allowed to know, the Anangu preferring to keep it to themselves.

On the other hand, the local Anangu community has a different interpretation. According to their belief, there was nothing on earth until their ancestors – in the forms of people, plants and animals — travelled widely across the land and formed the world as we know it. The spirits of these ancestors reside in Uluru which is sacred and it is the place where the spirits of the dead travel to rest for eternity. A visit to the rock not only enables them to invoke the spirits of the creators but also to speak to the spirits of their dead. Additionally, it is the site for a number of ceremonies: initiations, marriages and funerals. The white people do not know much about the Aboriginal culture here because we are not allowed to know, the Anangu preferring to keep it to themselves.

The Anangu people have only had regular contact with the white settlers for the past 60 years and, despite living in a purpose-built town with running water, electricity and cars, we did not see one of them in our three day visit. The elders still hold on to their traditional ways fiercely, not allowing any visitors to come to their community and keeping contact to the outside world to a minimum. In fact, even the didgeridoo player who came to our hotel to play at sunset was white.

The Anangu people have only had regular contact with the white settlers for the past 60 years and, despite living in a purpose-built town with running water, electricity and cars, we did not see one of them in our three day visit. The elders still hold on to their traditional ways fiercely, not allowing any visitors to come to their community and keeping contact to the outside world to a minimum. In fact, even the didgeridoo player who came to our hotel to play at sunset was white.

While most of us consider climbing Uluru to be a highlight, a rite of passage even, of a trip to the Red Centre, the locals do not like anyone to climb their sacred rock. The path to the top is a route taken by their ancestors on their arrival at Uluru and has great spiritual significance. At the base, near to the start of the track is sign that says ‘We don’t climb and request that you don’t either’. Being the custodians of the rock, they take responsibility for the safety of visitors and, apparently, it is a source of sadness and distress to them if a visitor is injured or dies on Uluru (and a surprising number of people manage to die each year mostly from falling or heart attacks).

For similar reasons of safety, Parks Australia would prefer that people did not climb either and the climb is closed about 80% of the time – if the temperature is forecast to be above 36c, if the wind is forecast to be more than 25 kph, if it is forecast to rain, or if one of the Anangu elders or a visitor has died. In fact, there was talk that the climb will be closed permanently soon which will have a considerable knock-on effect on tourists who believe that there is not much else to do around here.

But there is plenty. The walk around the base of the rock is a 9km stroll that would be very pleasant were it not for the hordes of flies who think that getting up my nose and into my mouth, ears and eyes is a pleasure worth fighting for. Unlike sensible Debbie, who had donned a fashionable fly net complete with camouflaged top (so from above the flies would be fooled into thinking she was a moving bush), I only had a cap, so I spent most of my time waving my hands around my head in a vain attempt to keep them away. At least, for me, the walk represented a complete workout!

But there is plenty. The walk around the base of the rock is a 9km stroll that would be very pleasant were it not for the hordes of flies who think that getting up my nose and into my mouth, ears and eyes is a pleasure worth fighting for. Unlike sensible Debbie, who had donned a fashionable fly net complete with camouflaged top (so from above the flies would be fooled into thinking she was a moving bush), I only had a cap, so I spent most of my time waving my hands around my head in a vain attempt to keep them away. At least, for me, the walk represented a complete workout!

The walk allowed us to get a close inspection of the rock revealing a wondrous pitted and contoured surface concealing numerous sacred sites. In the strong sunshine, the colour of the rock is a vibrant, strong red as the iron composition shines brightly. Most of the soft stone surface is smoothed by the elements but there are pockets of large divots where a chunk of the surface has either crumbled or fallen away leaving a scar of pock-marked interior. When the rain comes, it turns Uluru into an enormous waterfall whose streams have worked vertical cuts between the layers of ancient rock and, in some places, there are a series of pool areas that these streams tumble into on their way to the base.

The walk allowed us to get a close inspection of the rock revealing a wondrous pitted and contoured surface concealing numerous sacred sites. In the strong sunshine, the colour of the rock is a vibrant, strong red as the iron composition shines brightly. Most of the soft stone surface is smoothed by the elements but there are pockets of large divots where a chunk of the surface has either crumbled or fallen away leaving a scar of pock-marked interior. When the rain comes, it turns Uluru into an enormous waterfall whose streams have worked vertical cuts between the layers of ancient rock and, in some places, there are a series of pool areas that these streams tumble into on their way to the base.

On our walk across the top of the rock there are many more of these pools dotted all around where rainfall gathers before spilling over the edge. While the casual observer would be forgiven for thinking that the top of the rock was flat, it’s not at all. Apart from the pools where water gathers, the top is a series of smooth, steep vertical undulations that makes walking a challenge and we found ourselves scrambling on all fours in several places. The wind was also very strong, too strong for any headwear and too strong to communicate except downwind. We were fortunate to get to the top having started the steep, challenging climb soon after sunrise and before the Park Rangers had a chance to close the ascent. Too windy was the verdict for today and, I suppose, if anyone was daft enough to stand on the edge, it would be dangerous. However, for the fortunate few, the views from the summit were magnificent. The flat land beneath us stretched away into a hazy horizon many miles away. Once again, we felt that we were on top of the world, experiencing that wonderful, heady intoxication of freedom that comes from observing the world from high places. In the clear morning air we could see the flat, red sands of the desert and the jagged edges of other nearby rocky outcrops, the Olga Range in particular (35km away to the west) and also Mount Connor, not dissimilar to Uluru, that some people stop at, photograph and return home thinking they have seen the real thing. We spent some time soaking up the wondrous views, happy and privileged that we had been able to spend some precious time on the top of this precious place.

On our walk across the top of the rock there are many more of these pools dotted all around where rainfall gathers before spilling over the edge. While the casual observer would be forgiven for thinking that the top of the rock was flat, it’s not at all. Apart from the pools where water gathers, the top is a series of smooth, steep vertical undulations that makes walking a challenge and we found ourselves scrambling on all fours in several places. The wind was also very strong, too strong for any headwear and too strong to communicate except downwind. We were fortunate to get to the top having started the steep, challenging climb soon after sunrise and before the Park Rangers had a chance to close the ascent. Too windy was the verdict for today and, I suppose, if anyone was daft enough to stand on the edge, it would be dangerous. However, for the fortunate few, the views from the summit were magnificent. The flat land beneath us stretched away into a hazy horizon many miles away. Once again, we felt that we were on top of the world, experiencing that wonderful, heady intoxication of freedom that comes from observing the world from high places. In the clear morning air we could see the flat, red sands of the desert and the jagged edges of other nearby rocky outcrops, the Olga Range in particular (35km away to the west) and also Mount Connor, not dissimilar to Uluru, that some people stop at, photograph and return home thinking they have seen the real thing. We spent some time soaking up the wondrous views, happy and privileged that we had been able to spend some precious time on the top of this precious place.

The nearby Olgas, now known as Kata Tjuta (many heads) are a striking group of 36 domed rocks huddled together, shoulder to shoulder forming deep valleys and steep-sided gorges. In many ways, they are as captivating as their prominent neighbour with the tallest rock, Mount Olga, rising 546 metres above the land, considerably higher than Uluru and requiring a full complement of mountain equipment to climb it. The main walking track is known as the Valley of the Winds, an 8km loop trail that traverses varying desert terrain and yields wonderful views of surreal boulders.

The nearby Olgas, now known as Kata Tjuta (many heads) are a striking group of 36 domed rocks huddled together, shoulder to shoulder forming deep valleys and steep-sided gorges. In many ways, they are as captivating as their prominent neighbour with the tallest rock, Mount Olga, rising 546 metres above the land, considerably higher than Uluru and requiring a full complement of mountain equipment to climb it. The main walking track is known as the Valley of the Winds, an 8km loop trail that traverses varying desert terrain and yields wonderful views of surreal boulders.

Our aim had been to begin the walk soon after dawn so that we could be rewarded with solitude and enabling us to appreciate the sounds of the wind and the bird calls carried up the valley. We had been told to listen to the silence and to hear the ancient spirits talking to us from the rocks so as to fully appreciate the magic of this sacred place. In the event, all that proved completely impossible when two buses pulled into the car park behind us spilling their load off teenage schoolchildren on to the trail. Instead of listening to the spirits and the bird calls, we listened to boys talking about cars and sport, girls talking about boys and the latest music. It was not quite the education we sought. Nevertheless, the walk was excellent and the views of the mountains, the gorges and the valleys were spectacular.

However, the most spectacular views are reserved for sunset, when the sun fades below the horizon and the colours of Uluru change complexion by the minute. The bright, crimson red of the afternoon rock, scored and pitted by dark shadows change to a burnished orange, then a series of deeper, darker reds before becoming maroon and almost charcoal as the sun retires for the day. Even at night, under the influence of a full moon, the rock stands strong and black against the light night sky. It is one of nature’s most wonderful shows and it is worth coming here to see this alone.

However, the most spectacular views are reserved for sunset, when the sun fades below the horizon and the colours of Uluru change complexion by the minute. The bright, crimson red of the afternoon rock, scored and pitted by dark shadows change to a burnished orange, then a series of deeper, darker reds before becoming maroon and almost charcoal as the sun retires for the day. Even at night, under the influence of a full moon, the rock stands strong and black against the light night sky. It is one of nature’s most wonderful shows and it is worth coming here to see this alone.

Our visit was special, very enjoyable and very rewarding. Everyone should find time to come here and to enjoy some of natural wonders of the Red Centre. We could have spent many more days here exploring other areas that we did not have time to and did not realize were here before we arrived. They will have to wait for another time.

No comments yet.