Day 1&2 – Drake Passage: 1000km of ocean between South America and Antarctica and, reputedly, the roughest waters in the world. I was so worried about being sea sick that I started to feel unwell after breakfast, 8 hours before boarding the boat. What a plonker! Our boat, The Antarctic Dream, was built in 1958 for the Chilean Navy and, at 80 long, is one of the smaller vessels taking visitors to the White Continent. Flat out and with the wind behind it manages 12 knots but, mostly, 9 or 10 is what we get and that makes for a slow voyage. Supposedly, it had been refitted in 2005 but the yard that did the work must have been using the old Ushuaian prisoners or a gang of blind men as nothing quite fitted properly. The owners have a way of making sure that no one notices these defects – it’s called seasickness.

Crossing the Drake is generally accomplished in 2 days, sometimes faster with smooth seas that are known as ‘Drake’s Lake’ or slower, as in our case, with crossings known as ‘Drake’s Shake’. For the first five hours it is calm while we navigate out of the Beagle Channel but then, as we enter the open sea, we are met with force 9 winds, the surf on top of the waves at 4 metres and the swell coming at us sideways. What joy! This was the last time we saw most of our fellow passengers until we finally enter the more protected waters of the South Shetland Islands and are allowed to promenade out on deck for the first time in 36hours. Having taken pills to counteract motion sickness, we survived remarkably well, managing to put in an appearance for every meal. But the sea sick pills make us dopey and I am more than usually slow witted. I find myself staring out of the window at the giant waves in fascination for long periods. I feel like I am a drugged up inmate of a lunatic asylum and, no doubt, this is to the delight of the captain and crew because we are not able to cause any trouble.

The trick to getting fed was to stuff as much into our mouths as possible before our food, drink and dining companions ended up on the floor. I was quite pleased with myself having chinned the windows but once. I also determined, through bitter and sometimes painful experience, that it is necessary to have 3 anchor points at any given moment if I am to remain stable. So, two feet and one hand works well, or two feet and one bottom (though getting seated square on the toilet is a separate challenge). It is surprising how normally simple tasks such as washing hands or the face becomes very difficult. Taking a shower is a bruising affair. Sleep tends to come through exhaustion: I am either bumping into Debbie (not advisable if more bruises are to be avoided) or being unceremoniously dumped on the floor, especially on night 2 when the seas were at their roughest. The best bet is to lie on my back with my arms and legs spread as much as my wife will allow and hope for the best. However, I would not want anyone getting the idea that we did not enjoy it – we laughed all the way!

Respite finally came in the evening when we approached the South Shetland Islands as the seas began to subside and we were allowed outside into fresh air. We saw our first humpback whale while being escorted by wandering albatrosses, storm petrels and other seabirds as we make our way to the first anchorage point since leaving Ushuaia. We had a celebratory glass of wine and whiskey with glacier ice happy that we had managed to survive the Drake Passage without any sickness.

Respite finally came in the evening when we approached the South Shetland Islands as the seas began to subside and we were allowed outside into fresh air. We saw our first humpback whale while being escorted by wandering albatrosses, storm petrels and other seabirds as we make our way to the first anchorage point since leaving Ushuaia. We had a celebratory glass of wine and whiskey with glacier ice happy that we had managed to survive the Drake Passage without any sickness.

***********************************

Our Antarctic exploration itinerary was as follows:

Sunday 10th January: Morning landing at Aitcho Island

Afternoon landing at Half Moon Island

Monday 11th January: morning landing at Cuverville Island

Afternoon landing at Neko Harbour

Tuesday 12th January: Early morning cruise along Lemaire Channel often dubbed ‘Kodak Gap’ for its stunning views between Booth Island and the Antarctic Continent. Morning landing at Petermann Island

Afternoon Zodiac cruise amongst the grounded icebergs at Pleneau Bay

Wednesday 13th January: Morning landing at Port Lockroy and Wiencke Island

Afternoon Whale Safari

Thursday 14th January: morning hot spring swim at Deception Island

Afternoon begin return to Ushuaia

Friday 15th and Saturday 16th January: Plod back through Drake’s Passage to the Beagle Channel via Cape Horn.

Sunday 17th January: Arrive Ushuaia at 7.00am and get thrown off the ship.

The Antarctic Continent, as proved by Scott’s first expedition in 1909, was originally part of the super continent Gondwana from which, besides others, Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica broke away several million years ago. It is a landmass almost completely covered in ice in total contrast to the Arctic which has no land. The Antarctic holds 90% of the world’s ice and 70% of the world’s fresh water but truly it is a desert having the snow equivalent of less than 3 inches (7 cm) of rain – a precipitation rate close to that of the Sahara Desert – falling over the interior of the continent per year. But snow and ice have been accumulating on Antarctica for millions of years: more than 15,600 ft (4,800 m) deep at its thickest with a mean depth of ice exceeding 6,500 ft (2,000 m). It is also the highest continent in the world with an average elevation of 8,000 ft (2,460 m) and the South Pole is at an elevation of 9,301 ft (2,860 m).

The Antarctic Continent, as proved by Scott’s first expedition in 1909, was originally part of the super continent Gondwana from which, besides others, Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica broke away several million years ago. It is a landmass almost completely covered in ice in total contrast to the Arctic which has no land. The Antarctic holds 90% of the world’s ice and 70% of the world’s fresh water but truly it is a desert having the snow equivalent of less than 3 inches (7 cm) of rain – a precipitation rate close to that of the Sahara Desert – falling over the interior of the continent per year. But snow and ice have been accumulating on Antarctica for millions of years: more than 15,600 ft (4,800 m) deep at its thickest with a mean depth of ice exceeding 6,500 ft (2,000 m). It is also the highest continent in the world with an average elevation of 8,000 ft (2,460 m) and the South Pole is at an elevation of 9,301 ft (2,860 m).

During summertime, it never gets dark. Where we are the sun dips below the horizon and, officially at least, we are in night time. But it is not dark. It is still light enough to be 7.00pm of a nice summer’s evening which is pretty disorientating when we wake up at 2 in the morning.

It is very cold. I am dressed in a thick base layer, then a t-shirt, then a windstopper, then a jumper and, finally, a parka. I also have 2 pairs of socks, leggings, trousers and waterproof over trousers. I am OK most of the time, but when the wind blows, I can still get cold to the bone. During the trip, I read about both of Scott’s Antarctic expeditions. How those guys survived trekking across the ice for four months in temperatures as low as -90c I cannot begin to imagine.

It is very cold. I am dressed in a thick base layer, then a t-shirt, then a windstopper, then a jumper and, finally, a parka. I also have 2 pairs of socks, leggings, trousers and waterproof over trousers. I am OK most of the time, but when the wind blows, I can still get cold to the bone. During the trip, I read about both of Scott’s Antarctic expeditions. How those guys survived trekking across the ice for four months in temperatures as low as -90c I cannot begin to imagine.

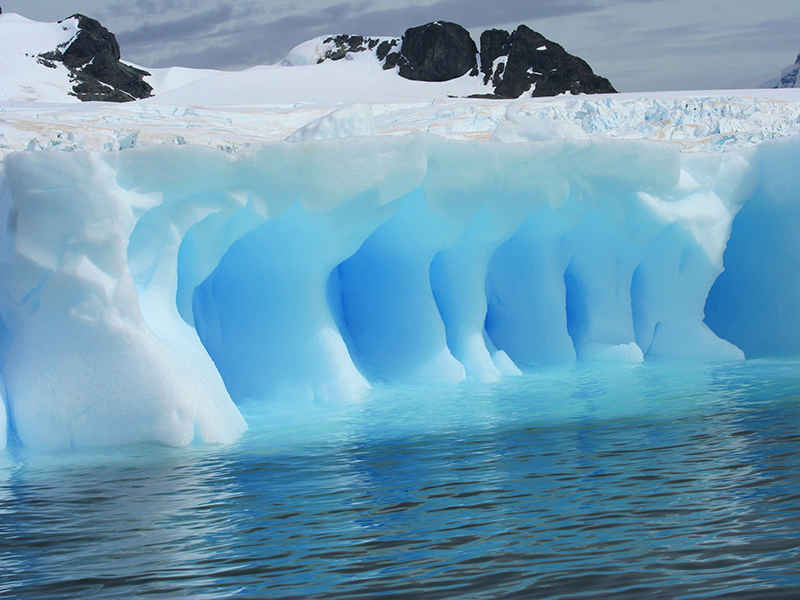

As can be imagined, there are icebergs everywhere. Mostly they are small and often cover the entire surface of the sea in the area that we are sailing but the ship bullies its way through them pushing them aside with little effort. Some are big and we have to avoid them, slaloming our way through channels that are flanked by angry looking black mountains. A few icebergs are truly enormous: we passed one during our first evening in the Antarctic that I estimated was easily the size of a football pitch in length and breadth and some 40 metres high. That was the 10% that is above the waterline! As I have now learnt that a cubic metre of glacial ice (it’s different to the ice we put into our drinks!) weighs about one ton, this berg is a 2 million ton colossus or about 1,000 times the weight of our ship!

As can be imagined, there are icebergs everywhere. Mostly they are small and often cover the entire surface of the sea in the area that we are sailing but the ship bullies its way through them pushing them aside with little effort. Some are big and we have to avoid them, slaloming our way through channels that are flanked by angry looking black mountains. A few icebergs are truly enormous: we passed one during our first evening in the Antarctic that I estimated was easily the size of a football pitch in length and breadth and some 40 metres high. That was the 10% that is above the waterline! As I have now learnt that a cubic metre of glacial ice (it’s different to the ice we put into our drinks!) weighs about one ton, this berg is a 2 million ton colossus or about 1,000 times the weight of our ship!

So glacial ice is very dense and, in its pure state, has a beautiful royal blue hue that we can see when it is ‘fresh’, that is to say when it is first exposed to the air and before the elements manage to turn the blue to the white colour with which we are all familiar. The jagged edges of the ends of glaciers can be a stunning contrast of bright blue and powder white especially when the sun breaks through the low cloud.

So glacial ice is very dense and, in its pure state, has a beautiful royal blue hue that we can see when it is ‘fresh’, that is to say when it is first exposed to the air and before the elements manage to turn the blue to the white colour with which we are all familiar. The jagged edges of the ends of glaciers can be a stunning contrast of bright blue and powder white especially when the sun breaks through the low cloud.

The Antarctic glaciers move at a rate of about 2cm per annum and not many chunks of ice fall into the sea. Where they do (and we were fortunate enough to witness some explosive fractures) they float about for years, melting very slowly due to their great density and the coldness of the sea. When the ship’s barman got hold of glacial ice for our evening tinctures, one small chunk would last all night.

The larger bergs invariably have fantastic shapes, all of which seem to be entirely unique. Given that they last for years and, in some places, do not move much, it must be possible to navigate using icebergs as reference points. I can recall one that looked like the Sydney Opera House and another that could have been the model for a cathedral. The bergs that are relatively flat topped, and not more than a metre above sea level invariably, are populated by different types of seals having a kip during the day between fishing expeditions.

The larger bergs invariably have fantastic shapes, all of which seem to be entirely unique. Given that they last for years and, in some places, do not move much, it must be possible to navigate using icebergs as reference points. I can recall one that looked like the Sydney Opera House and another that could have been the model for a cathedral. The bergs that are relatively flat topped, and not more than a metre above sea level invariably, are populated by different types of seals having a kip during the day between fishing expeditions.

We saw four different species of seals: the huge Elephant, the spotted and very fast & dangerous Leopard who is a serious predator in the seas, the docile Crab Eaters, and the very pretty Weddell. They are all chunky beasts coated in blubber against the cold but amazingly agile in the water. The Leopard seal likes to eat Penguin, itself faster under the water than any man can sprint, so these large lumps of lard have to be able to twist and turn with gymnastic contortion or go hungry. By contrast, when they are on land they are slow cumbersome creatures. They laze about semi somnolent scratching their face and chest with the claws on the end of their front flippers, occasionally lifting their head to observe what we are up to before returning to sleep.

We saw four different species of seals: the huge Elephant, the spotted and very fast & dangerous Leopard who is a serious predator in the seas, the docile Crab Eaters, and the very pretty Weddell. They are all chunky beasts coated in blubber against the cold but amazingly agile in the water. The Leopard seal likes to eat Penguin, itself faster under the water than any man can sprint, so these large lumps of lard have to be able to twist and turn with gymnastic contortion or go hungry. By contrast, when they are on land they are slow cumbersome creatures. They laze about semi somnolent scratching their face and chest with the claws on the end of their front flippers, occasionally lifting their head to observe what we are up to before returning to sleep.

I thought I might try out a little seal joke on Roger, the head of excursions and the boss of the naturalists. He is a Californian who tries very hard but never uses one word when he can use three, never uses one sentence when a whole paragraph can be employed. It is a question and answer joke that teenagers would use and goes like this:

Question: How do you know if two elephant seals have been making love in your swimming pool?

Answer: Because half the water’s gone and the dustbin liner’s missing.

‘So, Roger, I have a question for you’

‘OK James, I will do my best to answer it.’

‘Roger, how can you tell if two elephant seals have been making love in your swimming pool?’

Long pause, then he says ‘well James, I am not the best person to ask that question. I am a geologist not a biologist.’

Another pause because I am temporarily stumped by this: He has not cottoned on at all. Debbie is sniggering.

‘OK Roger. The answer is because half the water’s gone and the dustbin liner is missing.’

‘Well James, I do know that elephant seals don’t make love in water they do it on land.’

Another pause. Again, I am stumped and Debbie , not able to control herself, is now laughing out loud. This confuses Roger.

‘What has dustbin liners got to do with it?’ He asks.

‘It’s the elephant seals having safe sex Roger.’

More silence, broken only by Debbie rolling in the snow.

‘Oh…… Oh right, I get it. Yes Once I saw an elephant seal’s penis and, I can tell you, it’s very large. Makes mine look very small!’

I can imagine.

Once again, I have managed spectacularly to misconnect with the American sense of humour even allowing for the fact that Roger is blond. Despite speaking (more or less) the same language, along with the French and Germans, they live on a different comedy level to us. In contrast, the Spanish are on the same wavelength unless the jokes have to be translated, in which case they fall flat on their faces anyway.

Penguins are not much better on land than the seals. They waddle about with a Charlie Chaplin gait, wings held wide for extra balance, but often falling flat on their face having slipped or tripped on ice. They try to minimize the number of falls they take by keeping to the same communal routes to and from their nesting areas and these routes become pathways through the snow that resemble the work of humans digging a route through snow from the front door to the road.

Penguins are not much better on land than the seals. They waddle about with a Charlie Chaplin gait, wings held wide for extra balance, but often falling flat on their face having slipped or tripped on ice. They try to minimize the number of falls they take by keeping to the same communal routes to and from their nesting areas and these routes become pathways through the snow that resemble the work of humans digging a route through snow from the front door to the road.

At this time of year the Penguins are busy looking after their young who are around 4 weeks old and are just a light grey bundle of fluff, entirely dependent upon their parents for food and shelter (nothing new there). Whilst one parent goes off to fill its stomach with fish for itself and its young, the other sits on the young and guards the nest against the predatory Skuas. The Skuas are ever present, swooping overhead looking for an unguarded young penguin to snatch. They often work in pairs, one distracting the parent whilst the other takes the youngster. Amazingly, the Skuas can be seen resting on rocks within the Penguin colony, apparently living side by side with their prey.

At this time of year the Penguins are busy looking after their young who are around 4 weeks old and are just a light grey bundle of fluff, entirely dependent upon their parents for food and shelter (nothing new there). Whilst one parent goes off to fill its stomach with fish for itself and its young, the other sits on the young and guards the nest against the predatory Skuas. The Skuas are ever present, swooping overhead looking for an unguarded young penguin to snatch. They often work in pairs, one distracting the parent whilst the other takes the youngster. Amazingly, the Skuas can be seen resting on rocks within the Penguin colony, apparently living side by side with their prey.

The Penguin colonies themselves are a chaotic mess of nests made from small stones strewn in haphazard fashion over a rocky outcrop. The area is coloured white and red from penguin pooh depending upon what they have been eating (white = fish, red = krill) and smells pretty ripe. The penguins have a powerful ejection system for pooh and often manage to cover one of their neighbours or a passing friend with the type of eau de cologne that will never sell in the shops. However, none of them seem to object to having their starched shirts splattered and many of our photographs show them heading seawards for a clean up looking as if they are returning from a drunken rowing club dinner ending with a food fight.

The Penguin colonies themselves are a chaotic mess of nests made from small stones strewn in haphazard fashion over a rocky outcrop. The area is coloured white and red from penguin pooh depending upon what they have been eating (white = fish, red = krill) and smells pretty ripe. The penguins have a powerful ejection system for pooh and often manage to cover one of their neighbours or a passing friend with the type of eau de cologne that will never sell in the shops. However, none of them seem to object to having their starched shirts splattered and many of our photographs show them heading seawards for a clean up looking as if they are returning from a drunken rowing club dinner ending with a food fight.

At every landing we came across colonies of penguins, mostly of the Gentoo variety. The different species often nest in the same areas so it is quite normal to see Chinstraps next to Gentoo and, in one colony, an odd Macaroni (outstanding because of his exotic colouring and fabulous bushy yellow eyebrows) miles from home. For the record there were plenty of Adele penguins as well. But I was disappointed that we did not see any Emperor penguins though this was down to my sketchy penguin knowledge as I had obviously forgotten that Emperors, unlike other penguins, have their young in winter and head north in summer to the relatively balmy climes of South Georgia. So there were no around.

At every landing we came across colonies of penguins, mostly of the Gentoo variety. The different species often nest in the same areas so it is quite normal to see Chinstraps next to Gentoo and, in one colony, an odd Macaroni (outstanding because of his exotic colouring and fabulous bushy yellow eyebrows) miles from home. For the record there were plenty of Adele penguins as well. But I was disappointed that we did not see any Emperor penguins though this was down to my sketchy penguin knowledge as I had obviously forgotten that Emperors, unlike other penguins, have their young in winter and head north in summer to the relatively balmy climes of South Georgia. So there were no around.

Undoubtedly, the animal highlight of the trip was the whales. Of course, we knew they are big beasts before we went but, seeing them close up, their colossal size holds our complete attention until they slip beneath the surface. Most of the whales we saw were either Minke or Humpback, the latter being the ones we saw at close quarters, and one sighting of Orca. During the early afternoon they seem quite content to laze about near the surface and seem unconcerned if a lucky zodiac full of tourists comes within a few metres, but in the early evening they start feeding, giving us an unforgettable show as they surge out of the sea with a mouthful of krill before crashing back down in an explosion of water. When feeding, these gargantuan mammals can move at pace and an agility unexpected from a beast weighing several tons.

Undoubtedly, the animal highlight of the trip was the whales. Of course, we knew they are big beasts before we went but, seeing them close up, their colossal size holds our complete attention until they slip beneath the surface. Most of the whales we saw were either Minke or Humpback, the latter being the ones we saw at close quarters, and one sighting of Orca. During the early afternoon they seem quite content to laze about near the surface and seem unconcerned if a lucky zodiac full of tourists comes within a few metres, but in the early evening they start feeding, giving us an unforgettable show as they surge out of the sea with a mouthful of krill before crashing back down in an explosion of water. When feeding, these gargantuan mammals can move at pace and an agility unexpected from a beast weighing several tons.

The most usual sight of a whale (because on the surface they look like black flotsam) is that of their tail fins when they dive. Tailfins, like fingerprints, are unique each whale being able to be individually identified from the patterns and markings of the underside. Thus we knew that the owners of our ship had not got a tame whale on a leash constantly going around the boat.

The most usual sight of a whale (because on the surface they look like black flotsam) is that of their tail fins when they dive. Tailfins, like fingerprints, are unique each whale being able to be individually identified from the patterns and markings of the underside. Thus we knew that the owners of our ship had not got a tame whale on a leash constantly going around the boat.

Whale watching is a cold affair. Standing on deck in the freezing Antarctic winds holding a camera at the ready, the fingers go through a process whereby they get very cold, then hurt a lot, then go numb. Once numb it can be guaranteed a whale will surface nearby whilst the fingers are unable to find or press the camera shutter button especially when the rest of the body is in a state of excitement. In addition, we found that the battery life of our camera dwindled to a couple of hours, or less if using the telephoto lens, and it was always a case of what would give out first, me or the camera.

We were magnificently rewarded on two occasions when a humpback came right alongside the ship. If I could have leant over the rails to water level I could have touched it. Up close, they are not pretty beasts being covered in barnacles, but, boy, are they enormous. The ones we saw must have been about 15 metres long, around 2 metres wide and just took up a lot of room. They stayed around the ship for 5 minutes or so before going off for dinner and they had everyone on board scampering about, pushing and shoving, barging for the best camera shots (except us, of course) and we all behaved just like a bunch of feral paparazzi.

One other memory that we will take away with us is the scenery. Big black behemoth mountains rising straight out of the sea and reaching up to the clouds, huge harsh white glaciers that run down to the water’s edge often displaying their royal blue core, the occasional pebble shoreline dotted with penguins and resting seals, all set off by a jet black sea. Why the sea here is black rather than blue is a question to which I never got a satisfactory answer.

One other memory that we will take away with us is the scenery. Big black behemoth mountains rising straight out of the sea and reaching up to the clouds, huge harsh white glaciers that run down to the water’s edge often displaying their royal blue core, the occasional pebble shoreline dotted with penguins and resting seals, all set off by a jet black sea. Why the sea here is black rather than blue is a question to which I never got a satisfactory answer.

Out trip down some of the channels was truly spectacular, the Lemaire Channel in particular in which the ship feels insignificant as it sails in waters 100 metres wide walled by mountains and icefields. When the sun comes out, and we were very fortunate with the weather, all we can do is stand and gawp. It is stark beautiful, cold, uninviting but riveting. We loved it.

The mountains are an extension of the Andes range that disappear underwater in Southern Patagonia and reappear on the Antarctic continent. Certainly, they are exactly the same colour and constitution but none are still active. One that used to be a great volcano is now called Deception Island. It is a perfect cone and has a narrow, barely navigable entrance into its crater. We edge our way in with the intention of having a swim in the hot spring waters of an undersea geyser and we all have our swimmers on under several layers of thermal clothing. But the weather had different ideas, even in the protection of the crater the wind was blowing at 60 km per hour roughing up the seas so that the captain refused to launch the zodiacs. The disappointment was palpable, nowhere more so than on the faces of the older male passengers who had charged their cameras especially for the chance to spot the unusual sight young female humans frolicking in the Antarctic Sea.

This being the last day of our visit to the White Continent and the weather having turned against us, we headed back to Argentina in a force 10 gale. I wondered whether I could last the journey back without taking any pills for seasickness (being an occasional sailor). That thought lasted about 15 minutes by which time anything, even spending another two days drugged up with dramamine, was preferable to feeling seasick.

Having started back some hours early and, therefore, having time in hand, we returned via Cape Horn, the southernmost point at the convergence of the oceans. It looks familiar resembling Cabo de Gata on Spain’s south east corner, a point we have passed often on our way to and from Sotogrande and Palma. The sea here was flat. I have no idea what the fuss is about.

So ended our Antarctic adventure. What a fabulous journey and an experience that we will never forget. Apart from the purgatory of crossing Drake’s Passage in both directions it was worth every penny and every second of our lives.

No comments yet.