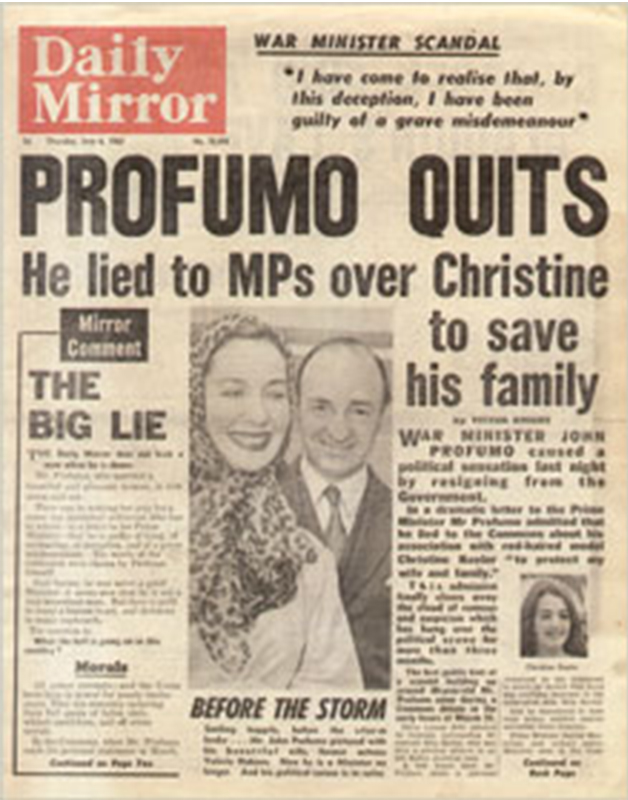

“There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanship with Miss Keeler.” Fifty years ago these words condemned Jack Profumo to public disgrace and, following the next election, the Macmillan government to opposition as a political scandal of tsunamic proportions enveloped Westminster. It wasn’t the first and certainly hasn’t been the last time that sex and politics have made incongruent bedfellows but it is probably the most infamous; The King of all Sex Scandals. But besides defining the political sex scandal, has the Profumo affair also provided a blueprint for redemption for the recalcitrant central character caught out by temptation?

After years of selfless charity work, and with the unremitting support of his wife, he eventually redeemed himself in the eyes of the Establishment; in 1975 he received a CBE from the Wilson government in recognition for his unremitting work on behalf of Toynbee Hall (an East End of London charity for the poor and down-and-outs), in 1982 he became its chairman (and later its president) and in 1995 he was seated at Her Majesty the Queen’s right hand for Margaret Thatcher’s 70th birthday party, signalling that he had at last been absolved of all his sins.

Tony Blair said of him, “He should be remembered with a lot of gratitude and respect for what he achieved in his later life.”

So, once he had fallen from grace, he devoted himself to charity work for the rest of his life – an outcome that reflected well on Profumo’s patrician sense of duty and decency. He never failed to bear his humiliations with dignity and personal integrity, refusing to speak about what had happened and never complaining about his treatment or seeking to excuse or justify in any way his actions.

Even in a secular society, the idea of forgiveness remains a central tenet of belief. It is fostered by the family unit and reinforced by religion and by the media (television in particular). Our judicial system sets tariffs for offenders as to how they must atone before their debt is paid to society. It seems, therefore, that every miserable offender can have a shot at redemption but what’s the best way to achieve it?

The quickest way to recovery is to confess early. This never happens because the perpetrator is too busy thinking about retaining their current life style and status, believing that they can get away with it by toughing it out, issuing denials, being angry, even threatening accusers with the law. This was Profumo’s initial response until evidence to the contrary became too great to hide and, a few weeks later, he was forced to resign admitting ‘with deep remorse’ that he had lied to the House of Commons. It’s the lying that is the problem. The electorate can forgive the affair but not the fact that they had been lied to.

It was the same with the Clinton/Lewinsky affair. The President insisting that “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky.” Only to have to admit that he did indeed have an ‘improper physical relationship’ after all. Like Macmillan’s Conservative government, the Democrats lost the next Presidential election as ‘Clinton fatigue’ overcame voters in a moral retrospective that terminally affected the chances of Al Gore.

Once confession has been made voluntarily or, more likely, involuntarily, the next essential step is to say a heartfelt sorry with maximum remorse to anyone willing to listen but without being too specific on the detail. Profumo wrote letters of profuse apology that were copied to the world via written media; Clinton engineered an emotional rendezvous with televised contrition. In the age of the 24/7 news cycle, this has become the medium du jour for forgiveness: Not only is it possible to get the words broadcast but also the sight of true contrition, supported by the ubiquitous tear, strikes to the very heart of public absolution. After all, every Hollywood Director recognises the value of the redemptive ending.

At this point the transgressor is required to disappear from public view. The point that no explanation, no excuse and no justification has been offered begins to play to the benefit of the redemption seeker. There is nothing for the public or the media to rail against other than the original offence and the milk of human kindness will start real or, more likely, imagined excuses flowing to their benefit. Clearly it helps enormously if the spouse sticks to their partner offering support and solidarity, blocking any attempt to squeeze tasty salacious scraps to a news hungry media.

The final ingredient for a successful redemption is charity work. Who has ever been criticised for that? Quite the opposite, in fact, we all admire those that give of themselves to charity whether it be time, money, expertise or a combination of all three. It has become an indispensible requisite of public life for anyone of substance. Though his wealth gave him an obvious cushion, Profumo was truly dedicated to his charity work with Toynbee Hall and not just as an attempt to rehabilitate his public image.

“Everyone here worships him”, a helper is quoted as saying. “We think he’s a bloody saint.”

Although he was happy cleaning out the toilets, an official said that they preferred him to concentrate on fund raising. From being an organisation about to go broke, the charity stabilised, growing its finances sufficiently to be able to establish a new and creative programme of services for the local people that included youth training schemes and facilities for people of all ages.

Bill Clinton also immersed himself in charity work, setting up the Clinton Foundation that concentrates on health issues. He hasn’t stuck at it like Profumo did but his charity is an important and influential conduit for health reform in a country where health treatment requires money. Although his redemption hasn’t obviously been achieved, it has been claimed that Clinton’s wholehearted support in the electoral stumpings for Barack Obama was an essential element of the Democrat’s Presidential Campaign.

Profumo’s redemption through charity work can come to symbolise goodness reasserting itself over evil. Not many public men disgraced since have been true to his example despite it being so obviously an ideal, a goal towards which they must strive without deflection. His story is of a man who made one terrible mistake and sought his redemption in unflinching, unheralded charity work that had no precedent in public life before. No one in public life ever did more to atone for his sins; no one behaved with more silent dignity and few ended their lives as revered by those who knew him.

The final word goes to his friend Lord Deedes: “The fact is what he did, and continued to do until quite recently, was a very long stint of charity work for the poor of East London. And if that isn’t considered to be sufficient atonement for the mistake he made, then there’s no such thing as forgiveness.”